Dear creative friends,

Welcome to Issue No. 48 of the Studioworks Journal! As always, I’m delighted you are here with me and I’m excited to share this with you. This month as we close out the year, I thought it might be lovely to dive into the world of fairytales! Why are they so prevalent in our culture, what kind of artists contributed to their popularity, and how can we be inspired by them?

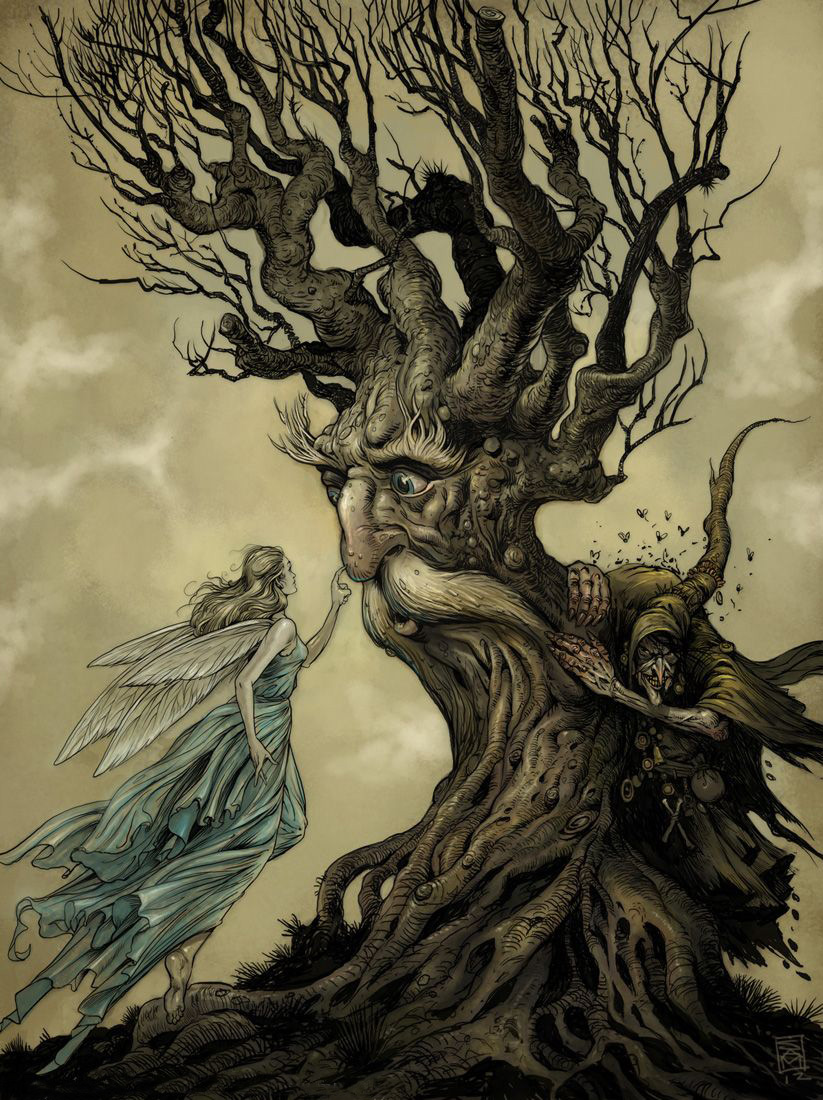

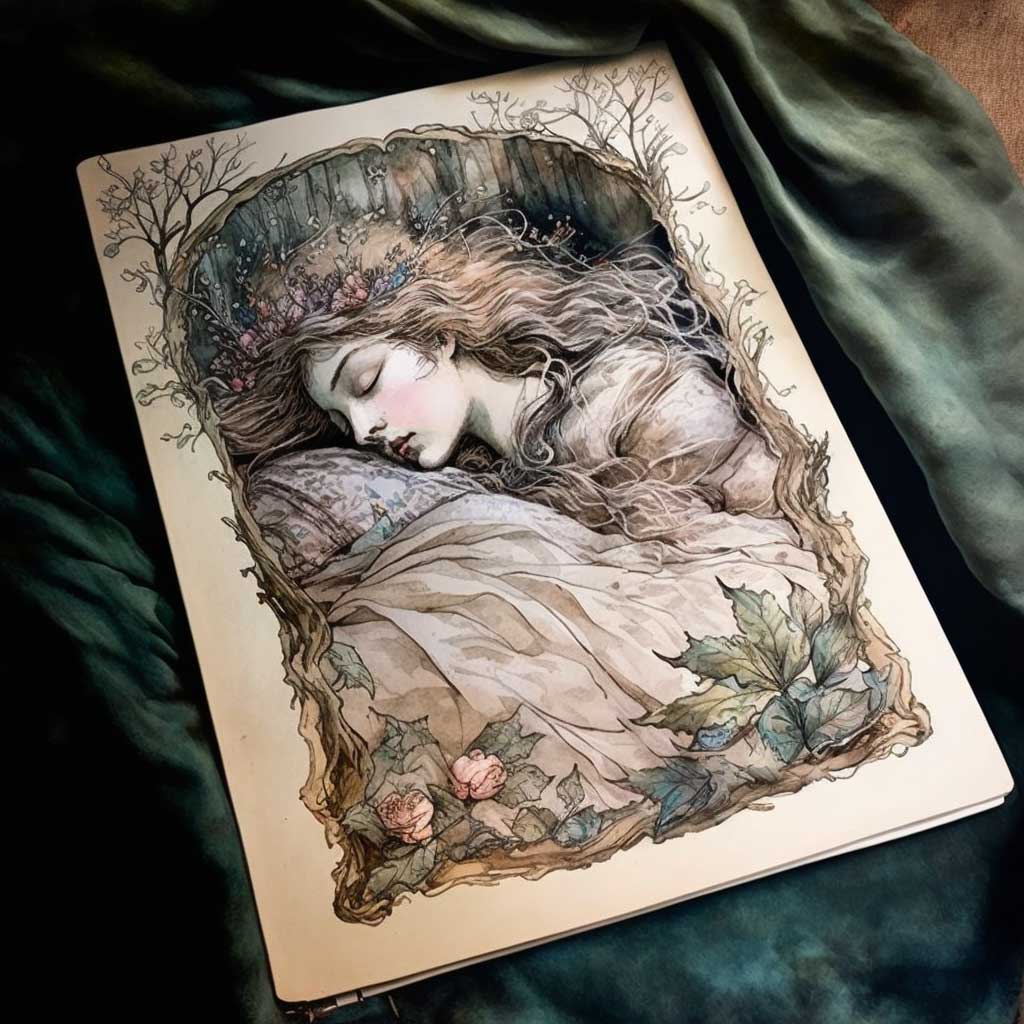

Fairytales are laden with dark monsters, dreamy heroes and heroines, fantasy worlds, whimsical characters, moral lessons, tragedy, and of course happy endings - well sometimes… I’m aware that many historical fairytales can be quite macabre but my intention is to stay on the lighter side!

Artists brought these tales to life with beautiful illustrations, etchings, paintings, and drawings so let’s take a peek into this topic, re-connect to our favorite childhood stories and make some fairytale art!

xo,

So you may be wondering, where do I start? To that, I say, wherever feels right to you. Each month we will have a theme, a creative affirmation, a power word, a color palette, sketchbook exercises, art projects, articles, recommended reading, and access to wonderful inspiration and resources. I want you to think of this as a delicious new magazine, you know the ones you occasionally splurge on, with soft, velvety pages, beautiful images, and inspiring content!

Each issue will invite you to explore your creative practice in whichever way works for you. Experience each issue at your own pace. Take what resonates with you and put the rest aside for another time.

Grab a cup of something lovely and dive in.

Fairytales and art have always gone hand in hand. Given the artistry involved in the writing style and the long lineage of illustrators and other artists inspired by the stories, this should come as no surprise. Since fairytales are frequently the mainstays of childhood, many of us can likely credit them with conjuring some of our earliest desires to make artistic creations of our own. It makes sense, how could imaginations fail to be stirred by tales of magical kingdoms populated with mystical creatures, talking animals, and grand adventures where good often prevails over evil?

Fairytales are all but begging to be turned into visual art, which explains the endless new renditions, remakes, and re-releases of these stories across various media, which tirelessly withstand the test of time. Given their adaptability and broad appeal, this is likely to remain true for the unforeseeable future.

Fittingly, the origins of fairytales are obscured in murky shadows. We know that they have played a pivotal part in human societies across the globe for centuries. In fact, researchers have done some fancy detective work to unveil that the oldest ones may predate literary records, going back some six thousand years to the Bronze Age.

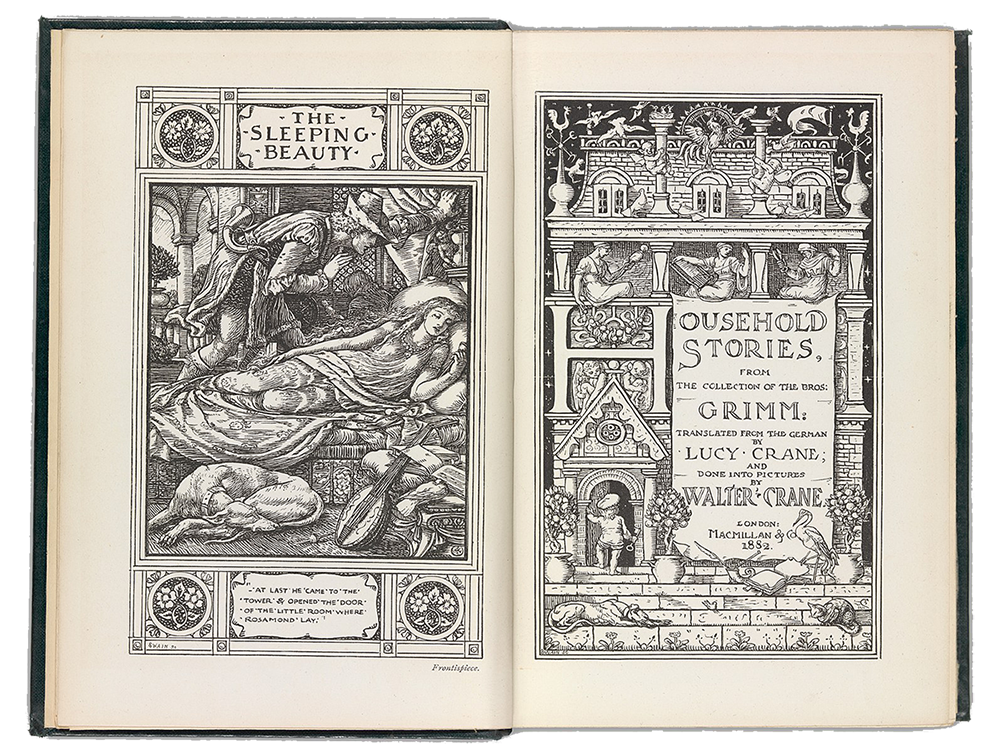

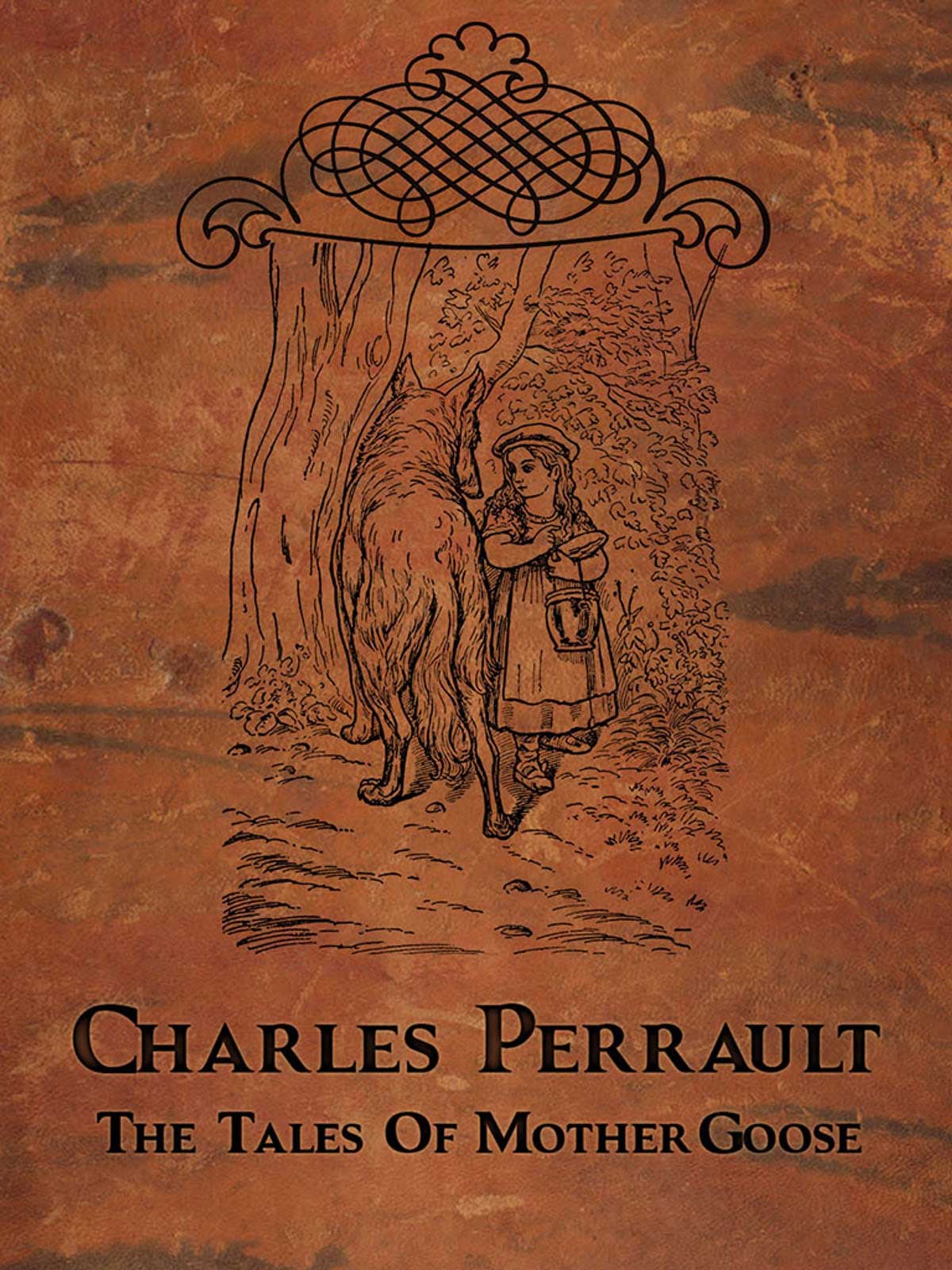

Initially, fairytales were shared via oral traditions, with cultural variations and shifting values adapted to meet the needs of the time. It wasn’t until the seventeenth century that some of these folk tales were compiled and published by Charles Perrault, concretizing specific versions for the first time. More than a century later, the Brothers Grimm created collections of their own containing many of the same or similar stories but popularizing a Germanic take on the tales that persists to this day.

Another influential 19th-century shaper of fairytale realms, Hans Christen Andersen, used the influence of Norse Mythology and the collected stories of Danish scholar Mathias Thiele to write his own fables. His efforts delivered some of the best-known and loved tales including, “The Ugly Duckling,” “The Little Mermaid,” and “The Emporer’s New Clothes."

The title of Charles Perrault’s book, Stories or Tales from Times Past, with Morals (also titled, The Tales of Mother Goose) makes no attempt to conceal the intention of the author to impart moral values to children. The Brothers Grimm were likewise inclined to guide their young readers, liberally using fear tactics as a form of persuasion. For example, the early versions of Little Red Riding Hood ended with both the protagonist and her grandmother being consumed by the wolf. An effective, if harsh, way to prevent young women from talking to strangers.

In a lighter sense, fairytales are accessible and entertaining ways to teach children about social dynamics, expectations, and values by creating engaging characters who overcome complex challenges. They are myths meant to help us recognize archetypes we’ll encounter across our lifespans and attempt to nudge our behavior in the direction of goodness. What this looks like continues to shift over time, revealing the mercurial nature of societal values and the profound impact that has on art.

A picture truly does speak a thousand words. Each artist that creates an image from a fairytale builds a world, shapes interpretation, and frames how the story is seen and remembered. Tellingly, each new edition of Perrault’s, Grimm’s, and Andersen’s books have been illustrated by yet another notable and often famous artist.

The urge to bring life to these impactful stories seems boundless, attracting artists as varied as one of the beloved founding fathers of the Arts and Crafts movement, William Morris, and the ethereally enchanting painter Maxfield Parrish.find fairytale illustration

The temperaments of the times and the artists are both reliably reflected in the style and delivery of fairytale images. From the dark and menacingly beautiful paintings of Aubrey Beardsley to the whimsical fancy of Adrienne Segur, no two interpretations are the same. These differences reflect the wild variations in how individuals conceive ideas and construct an image. An inspiring reminder that each of us has something unique to conjure.

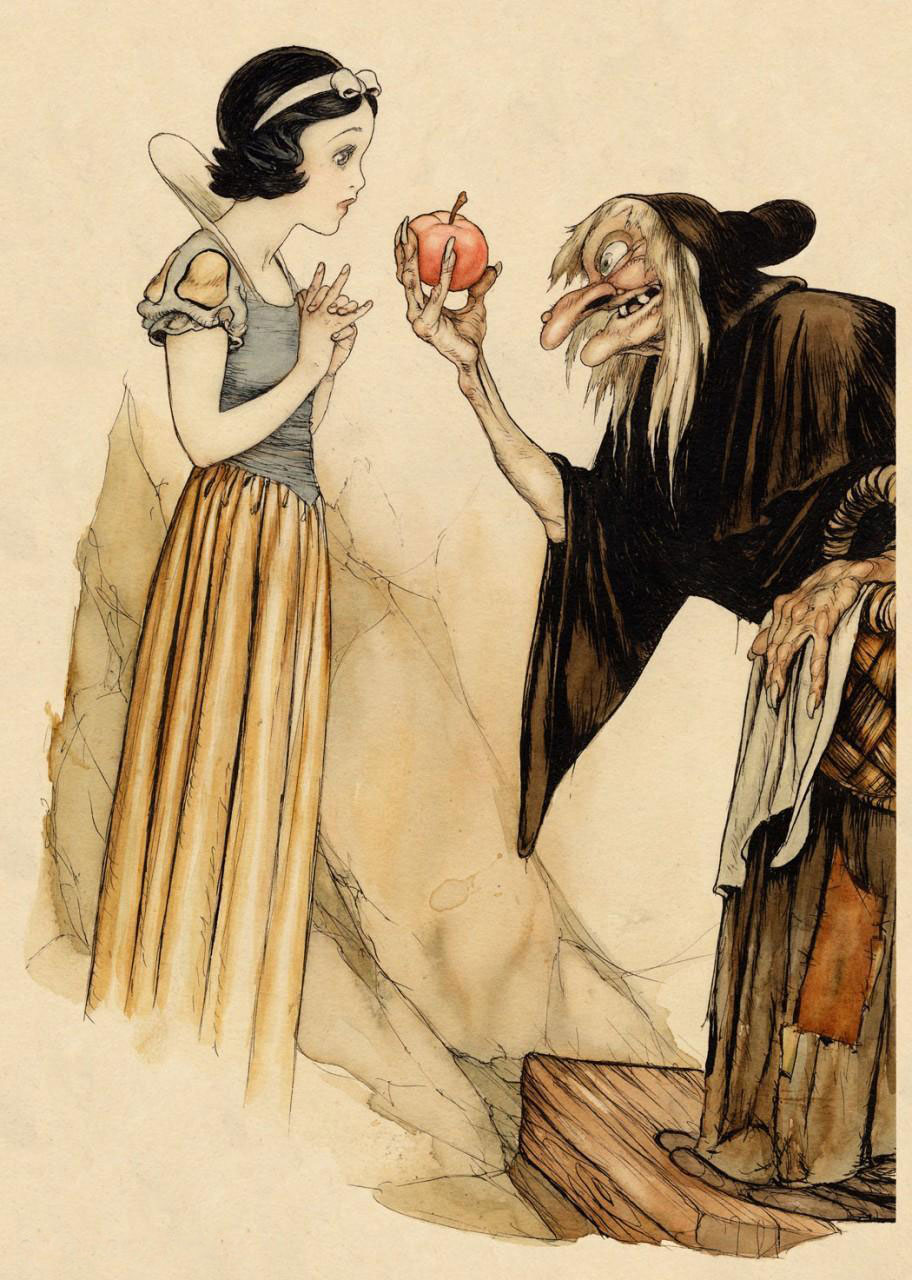

The visuals that populate book and movie adaptations of fairytales double-down their impact, often carving indelible images in the minds of viewers, young and old. The still of the witch handing Snow White a poisoned apple from Disney’s first animated film is a fine example.[4] Another is the eerily beautiful rendering of Little Red Riding Hood by Harry Clarke from a 1922 edition of The Fairy Tales of Charles Perrault.[5] In fact, the number of images conveying the girl in red and her wolfy adversary are among the most varied and ubiquitous, leaving few children without a vivid personal recollection.

The number of iconic images is too staggering for inclusion, but the takeaway is clear: fairytales and art are two peas in a pod. Fortunately, their dynamic is not irritating like that of the Princess and the Pea, but rather a union that continues to inspire, yielding iconic, beautiful, creative, and enduring progeny.

Anything meant to endure needs to be well constructed. In this, stories are no different. A fundamental reason fairytales have played a pivotal role in human society throughout history, is that they are deliberately, painstakingly, and lovingly crafted.

The fairytale formula is definitive enough that scholars, after poring over stories from around the globe and across the ages, have generated an essential recipe. There are many variations, but the following nine ingredients typically find themselves in the mix:

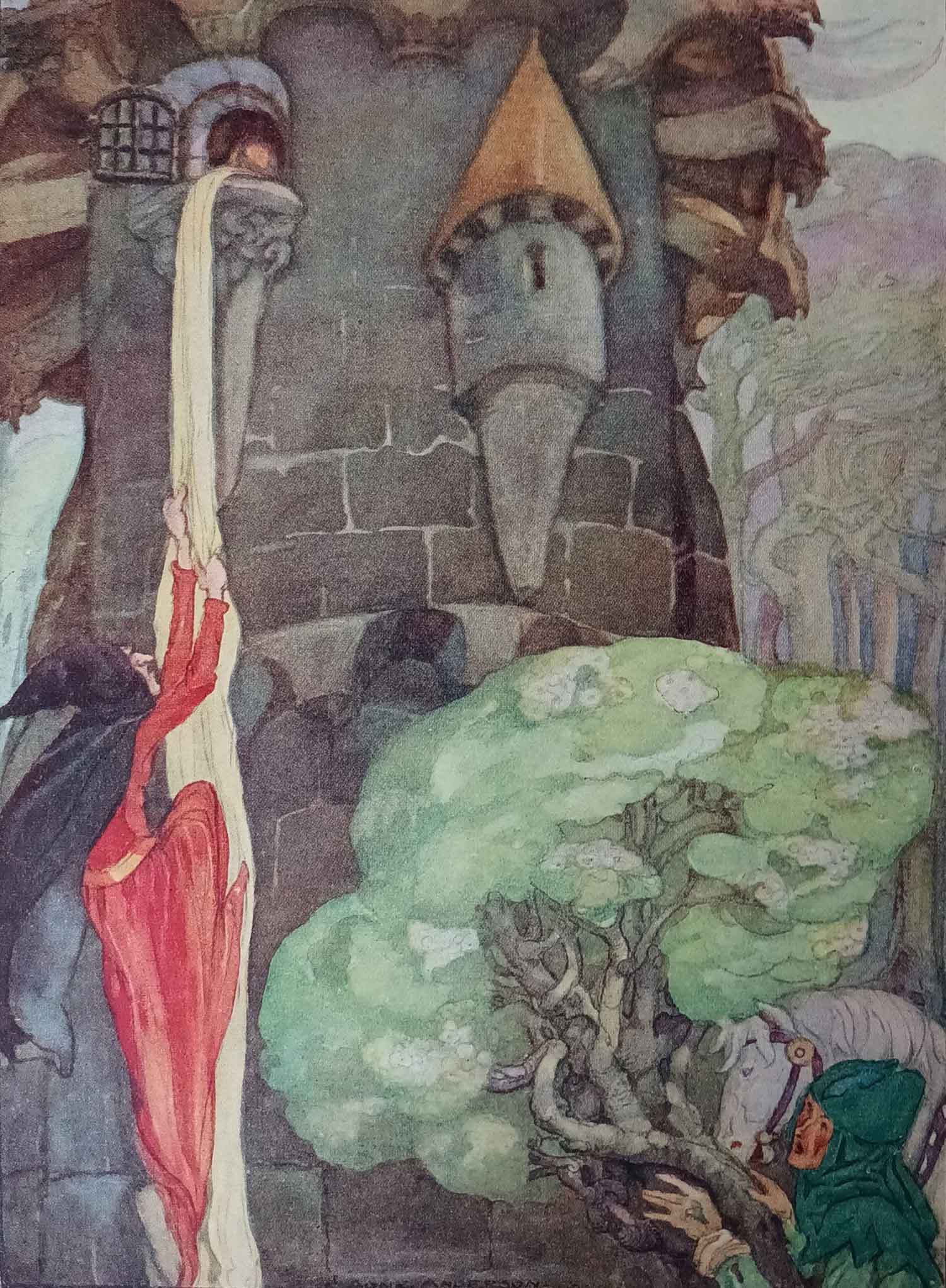

An illustrator who embarks on the herculean task of bringing fairytale images to life must understand the underpinning symbolism and essential ideas necessary to the story. For example, the hero or heroine must seem pure, unworldly, and open to the miraculous. The villain must be crafty, manipulative, and willing to use power for evil purposes. There also needs to be friends/allies/sidekicks who are mysterious, perhaps magical, and frequently give gifts to the hero.

In addition, the use of light colors to impart purity and innocence is common, just as the darker palette is often used to suggest malicious machinations and wickedness. Black, white and red, are frequently encountered colors, as the titles Snow White, Blackbeard, and Little Red Riding Hood reflect. In general, colors are deliberately used to convey significance, but not always of the same kind. For instance, red might represent vitality, courage, and liveliness, in one story, and death, fire, and brimstone in another. The important thing is that the artist grasps this and uses colors accordingly.

Another typical fairytale component is the incorporation of magical numbers, most frequently three and seven. These numbers have long-standing significance around the world. For example, three evokes the power of the holy trinity, and seven signifies the day of rest after God created the universe. Furthermore, three represents the Greek Fates of Birth, Lifespan, and Death. It also holds a deep import in Norse and Egyptian Mythology, representing the three realms of Nilfhelm, Midgard, and Asgard for the former, and the trinity of Osirus, Isis, and Horus for the latter.

Seven also shows up across cultures and ages, representing cosmological components like the seven original planets and the seven stars of the Pleiades, seven virtues and sins, and the magical abilities granted the seventh son of the seventh son (to name a few). These numbers might play out as seven dwarves, three pigs, seven degrees of initiation, or three days to complete a task, but they undoubtedly show up again and again in fairytales.

An example that beautifully captures some of the aforementioned elements, is an illustration of Rapunzel by Anne Anderson from a collection of Grimms Fairy Tales.[4] The maiden is obscured in the tower, you only glimpse her pure golden hair. The evil witch is sinister in color and form as she begins her ascent of the hair. Hidden behind a tree are the awestruck prince and his loyal steed. Rapunzel’s prison tower is dark and foreboding, but the surrounding landscape is soft with pastel hues of pink, green, and blue. The tension between good and evil is palpable in the scene.

Another fine demonstration of fairytale symbolism is an illustration of Hansel and Gretel by Charles Robinson. This Art Nouveau-inspired piece depicts the child protagonists with bright, innocently upturned faces, with feet mired in the shadows of the darkening woods that seem to be in the act of swallowing them. Again, the play of purity versus darkness is evident and artfully executed.[5]

To conclude, it seems appropriate to give a nod to the symbology of numbers and the role of film in the continued popularity of fairy tales. How better than to mention Gustaf Tenggren’s poster for the 1937 premier full-length Disney film, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs?[6] This image has it all: significant numbers, darkness and light, heroes/heroines, evil witches, fanciful friends, and a castle to live in, “Happily ever after.” This poster brings all the pieces together, something that makes for a happy ending.

Get those journals and sketchbooks out and get ready to do some self-reflection and writing. Try not to judge what comes out of these writing sessions. Don’t worry about punctuation or grammar or any of that. You can even just make lists if that suits you better.

Take a moment to get quiet. Still yourself by doing some gentle breath work. Light a candle. Now ask yourself some questions to reflect upon -

• When you think of your favorite fairytales what story comes to mind first?

• Why does this story stand out for you? What memories or imagery are tied to it for you?

• What fairytale do you like the least? Why?

• If you had to choose to illustrate one fairytale, which one would it be?

I laughed out loud when I read the definition of “quest”! It sounds exactly how I would describe my art journey! Lol. I’m sure you can relate, just like the heroes in a fairytale, us artists are on a very serious quest - whether we know it or not! To further the definition, I would say that it is a long arduous search for something that is so often intangible. A feeling more than an outcome, a longing more than a need. Ultimately, I believe that artists are questing for the truest expression of themselves. Lucky for us and all our favorite art stores, this quest lasts a lifetime.

I am sharing this beautiful Meditation from one of my favorite meditation masters - Rachel Hillary. When I think of my favorite fairytales my heart certainly swells a little bit so I thought a heart center meditation would support us this month.

Rachel will share a little about this experience -

I had the feeling recently of divine energy flowing through our hearts, bringing through our celestial heart energy to earth at this powerful time, merging the earth with the divine. This meditation will connect you to this heart energy, allowing it to gently expand and flow. Please note there is no ending bell, just gentle words followed by music fading out if you wish to drift off to sleep.

lots of love,

Rachel

Each month we will have a positive affirmation. I recommend you print out this affirmation and put it in your sketchbook or somewhere in your studio. Recite the affirmation out loud each time you show up to create. Saying words aloud is powerful and can begin to re-write some of our own limiting beliefs or calm our fears. Try it now…

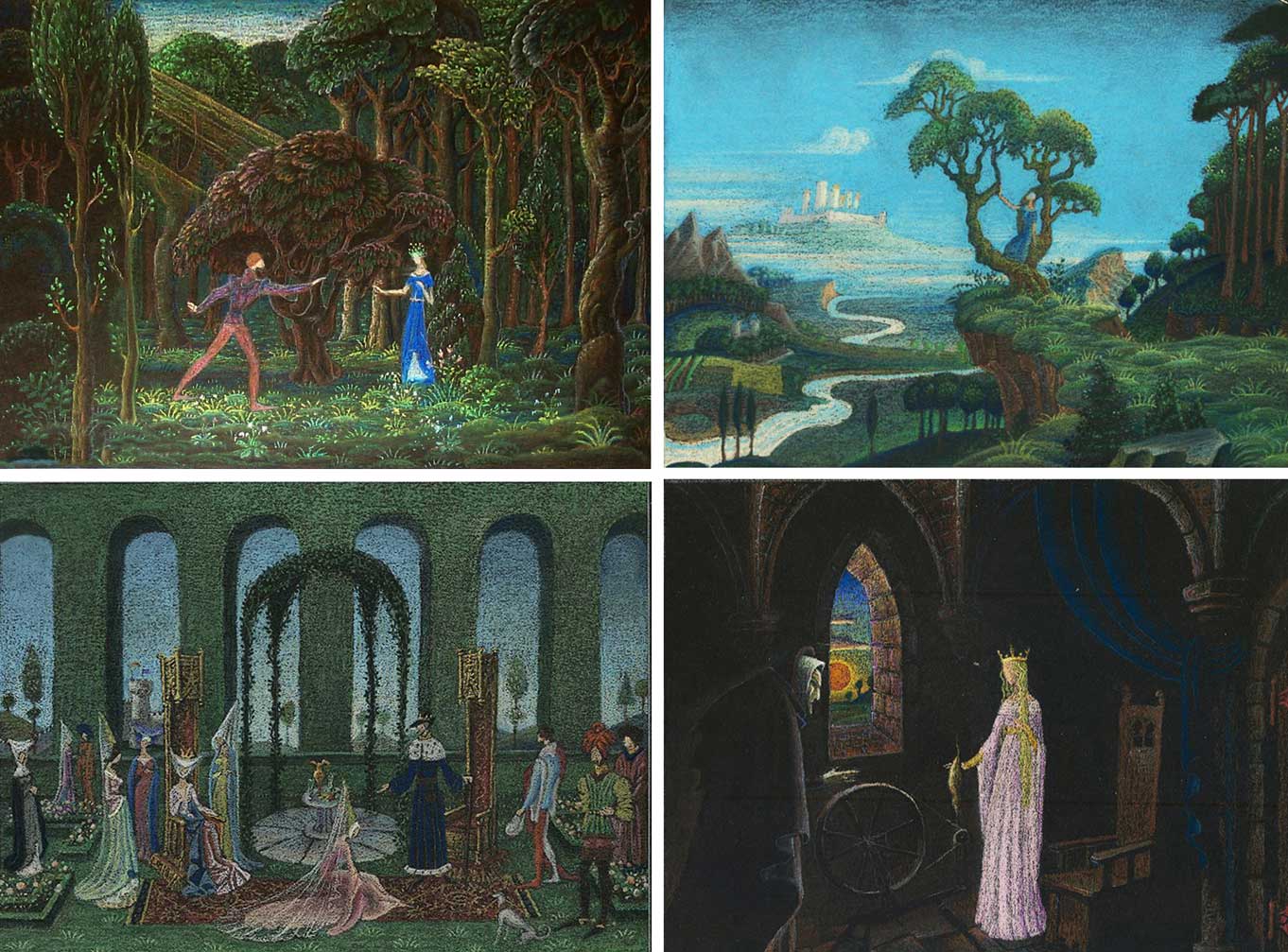

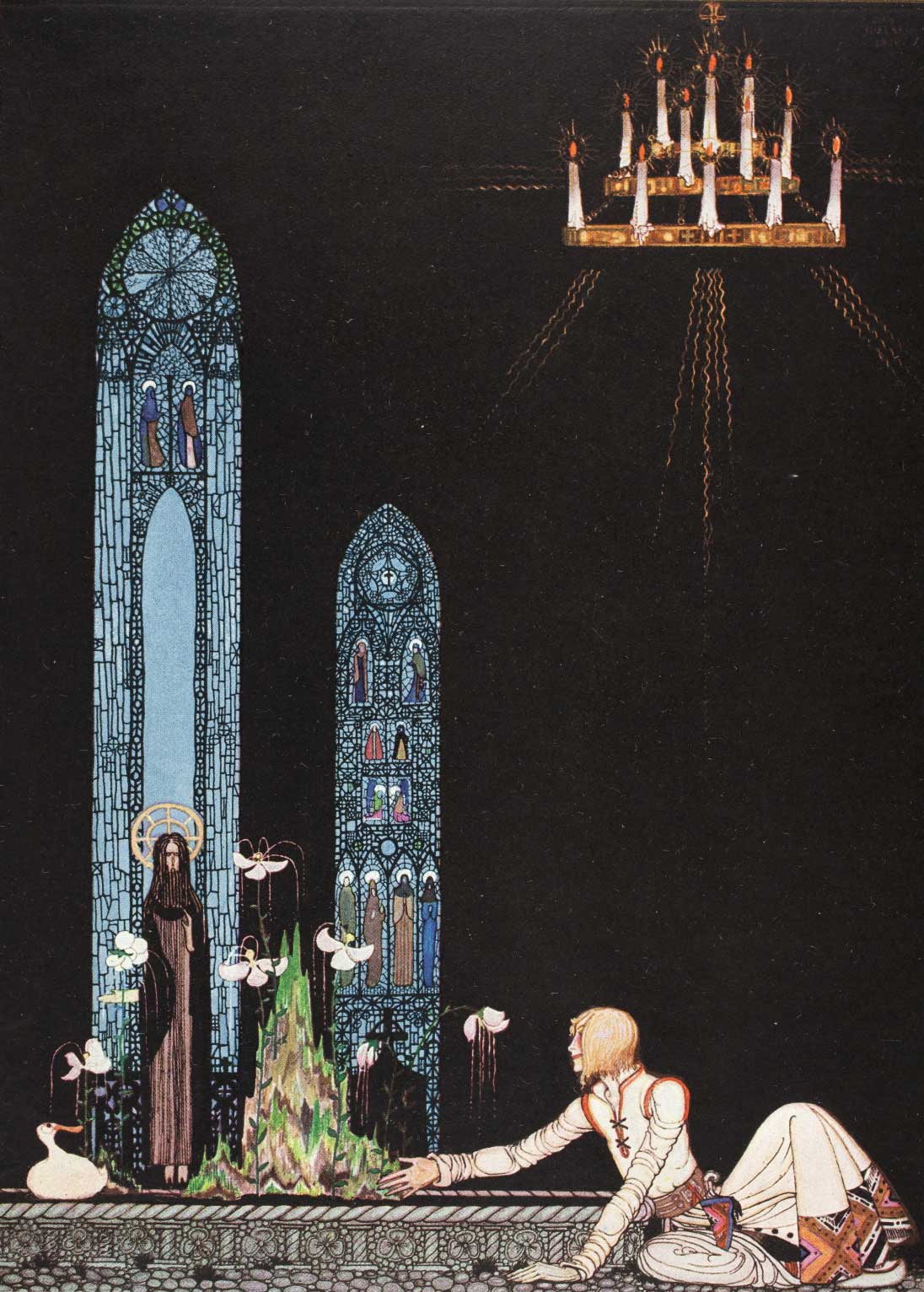

This month I am inspired by the gorgeous illustrations of our two Master Artists, Kay Nielsen and Arthur Rackham. Both artists employ soft hues and intricate line work to express the various scenes they depict from our most beloved tales. I love the ethereal, yet atmospheric effect of using subtle layers of color with the contrast of heavy ink line work. So let’s explore this juxtaposition…

As always, work with colors that call to you and never doubt your creative intuition. Your colors may look entirely different and that’s ok.

For this issue, I couldn’t pick just one Master Artist who illustrated fairytales so we will be looking at two - Kay Nielsen and Arthur Rackham. Both artists created whimsical beauty and intricate details in their illustrations and both artists created art for some of the most well know fairytale stories. Let’s marvel at their skill and imagination!

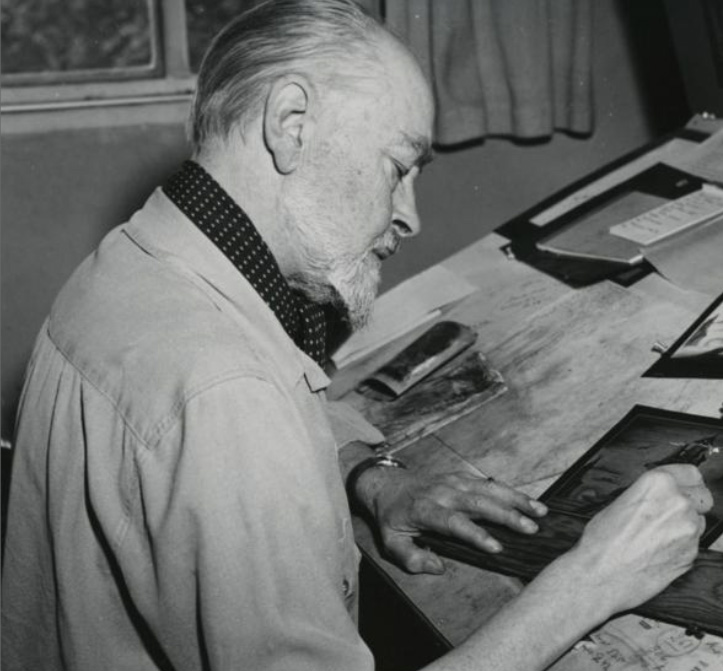

Kay Rasmus Nielsen (March 12, 1886 – June 21, 1957) was a Danish illustrator who was popular in the early 20th century, the Golden Age of Illustration. Nielsen is also known for his collaborations with Disney for whom he contributed many story sketches and illustrations, not least for Fantasia.

Kay Nielsen was born in Copenhagen into an artistic family; both of his parents were successful actors. Kay Nielsen studied art in Paris at Académie Julian and Académie Colarossi from 1904 to 1911 and then lived in England from 1911 to 1916. He received his first English commission from Hodder and Stoughton to illustrate a collection of fairy tales, providing 24 color plates and more than 15 monotone illustrations for In Powder and Crinoline, Fairy Tales Retold by Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch in 1913. In the same year, Nielsen was also commissioned by The Illustrated London News to produce a set of four illustrations to accompany the tales of Charles Perrault; Nielsen's illustrations for 'Sleeping Beauty', 'Puss in Boots', 'Cinderella' and 'Bluebeard' were published in the 1913 Christmas Edition.

A year later in 1914, Nielsen provided 25 color plates and more than 21 monotone images for the children's collection East of the Sun and West of the Moon. Also in that year, Nielsen produced at least three illustrations depicting scenes from the life of Joan of Arc. When published later in the 1920s, these images were associated with relevant text from The Monk of Fife.

While painting landscapes in the Dover area, Nielsen came into contact with The Society of Tempera Painters where he learned new skills, and was able to reduce the time involved in the painting process. In 1917 Nielsen left for New York where an exhibition of his work was held and subsequently returned to Denmark. Together with a collaborator, Johannes Poulsen, he painted stage scenery for the Royal Danish Theatre in Copenhagen. During this time, Nielsen also worked on an extensive suite of illustrations intended to accompany a translation of The Arabian Nights that had been undertaken by the Arabic scholar, Professor Arthur Christensen. According to Nielsen's own published comments, these illustrations were to be the basis of his return to book illustrations following a hiatus during World War I and the intention had been to publish the Danish version in parallel with versions for the English-speaking world and the French market. The project never came to fruition and Nielsen's illustrations remained unknown until many years after his death.

During the 1920s, Nielsen returned to stagecraft in Copenhagen designing sets and costumes for professional theater. During that time, at age 40, he married the charismatic 22-year-old Ulla Pless-Schmidt, daughter of a wealthy physician, and they became a devoted couple. At this point, he was Scandinavia's most famous artist.

Following his theatrical work in Copenhagen, Nielsen returned to contributing to illustrated books with the publication of Fairy Tales by Hans Andersen in 1924. That title included 12 color plates and more than 40 monotone illustrations. A year later, Nielsen provided the artwork for Hansel and Gretel, and Other Stories by the Brothers Grimm which was first published with 12 color images and over 20 detailed monotone illustrations. A further 5 years passed before the publication of Red Magic, the final title to be illustrated comprehensively by Nielsen. The 1930 version of Red Magic included 8 colors and more than 50 monotone contributions from the Danish artist.

In 1939 Nielsen left for California and worked for Hollywood companies. A personal recommendation from Joe Grant to Walt Disney secured Nielsen a job with The Walt Disney Company where his work was used in the Night on Bald Mountain/Ave Maria sequences of Fantasia. Nielsen was renowned at the Disney studio for his concept art and he contributed artwork for many Disney films, including concept paintings for a proposed adaptation of Hans Christian Andersen's The Little Mermaid. The adaptation was to be part of a package film containing various segments based on Andersen's fairy tales. The film, however, was not made within Nielsen's lifetime and his work went unused until production started on the 1989 film. Nielsen worked for The Walt Disney Company for 4 years, from 1937 to 1941 before being let go.

Nielsen briefly returned to Denmark in desperation. However, he found his works no longer in demand there either. His final years were spent in poverty. His last works were for local schools, including 'The First Spring' mural installed at Central Junior High School, Los Angeles and churches, and his painting for the Wong Chapel at the First Congregational Church, Los Angeles, illustrating the 23rd Psalm.

A heavy smoker, Nielsen contracted a chronic cough that would plague him until his death on June 21, 1957 at the age of 71. His funeral service was held under his mural in the Wong Chapel. His wife, Ulla, died the following year.

Before her death to diabetes, Ulla gave Nielsen's remaining illustrations to fellow artist and architect Frederick Monhoff, who in turn tried to place them in museums. However, none – American or Danish – would accept them at the time.

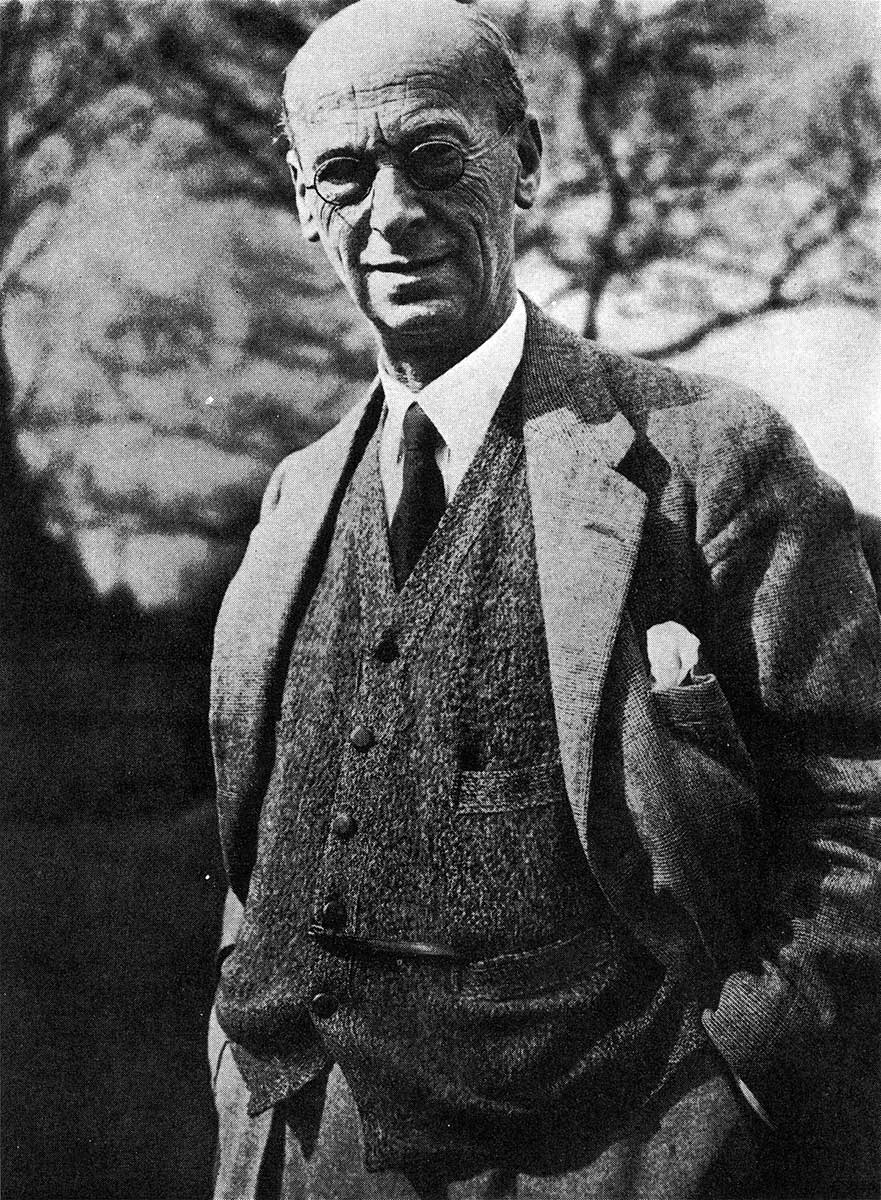

Arthur Rackham (19 September 1867 – 6 September 1939) was an English book illustrator. He is recognized as one of the leading figures during the Golden Age of British book illustration. His work is noted for its robust pen and ink drawings, which were combined with the use of watercolor, a technique he developed due to his background as a journalistic illustrator.

Rackham's 51 color pieces for the early American tale Rip Van Winkle became a turning point in the production of books since – through color-separated printing – it featured the accurate reproduction of color artwork. His best-known works also include the illustrations for Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens, and Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm.

Rackham was born at 210 South Lambeth Road, Vauxhall, London as one of 12 children. In 1884, at the age of 17, he was sent on an ocean voyage to Australia to improve his fragile health, accompanied by two aunts. At the age of 18, he worked as an insurance clerk at the Westminster Fire Office and began studying part-time at the Lambeth School of Art.

In 1892, he left his job and started working for the Westminster Budget as a reporter and illustrator. His first book illustrations were published in 1893 in To the Other Side by Thomas Rhodes, but his first serious commission was in 1894 for The Dolly Dialogues, the collected sketches of Anthony Hope, who later went on to write The Prisoner of Zenda. Book illustrating then became Rackham's career for the rest of his life.

By the turn of the century, Rackham had developed a reputation for pen and ink fantasy illustration with richly illustrated gift books such as The Ingoldsby Legends (1898), Gulliver's Travels and Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm (both 1900).

In 1901 he moved to Wychcombe Studios near Haverstock Hill, and in 1903 married his neighbor Edyth Starkie. Edyth suffered a miscarriage in 1904, but the couple had one daughter, Barbara, in 1908. Although acknowledged as an accomplished black-and-white book illustrator for some years, it was the publication of his full-color plates to Washington Irving's Rip Van Winkle by Heinemann in 1905 that particularly brought him into public attention, his reputation being confirmed the following year with J.M.Barrie's Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens, published by Hodder & Stoughton. Income from the books was greatly augmented by annual exhibitions of the artwork at the Leicester Galleries. Rackham won a gold medal at the Milan International Exhibition in 1906 and another one at the Barcelona International Exposition in 1912. His works were included in numerous exhibitions, including one at the Louvre in Paris in 1914. Rackham was a member of the Art Workers' Guild and was elected its Master in 1919.

From 1906 the family lived in Chalcot Gardens, near Haverstock Hill, until moving from London to Houghton, West Sussex in 1920. In 1929, the family settled into a newly built property in Limpsfield, Surrey. Ten years later, Arthur Rackham died at home of cancer.

• Delicate, detailed ink work

• Use of pen and ink and watercolor

• Flat use of space (no perspective)

• Detailed patterns

• Soft or subdued colors

• Rhythmic or lyrical use of swirling lines to create movement

• Often a vertical composition - suitable for book format

• Art Nouveau and Art Deco or Pre-Raphealite influence

• Often influenced by Japanese woodcut art and composition

• Annie French

• Edmond Dulac

• Gustave Doré

• Anne Anderson

• John Bauer

• Adrienne Ségur

• Virginia Frances Sterrett

• Jessie M. King

• Warwick Gob

Try your hand at illustrating a scene from your favorite fairytale. It can be in any style and any medium. Let yourself get lost in the story and your imagination wander as you design your sketch or painting. Feel free to use collage or tracing to assist you in conveying your expression of the scene.

Take a peek at our Pinterest board full of inspiring images created by history’s best fairytale illustrators. Pick one to do a study of or create a piece inspired by the selected work. Have fun with this! Many of these illustrators used pen and ink and washes of watercolor to create their pieces. Use these mediums if they appeal to you!

If you were to create your own fairytale who would be your main character? What would your hero or heroine look like? Would they be a young girl? A fairy? A good queen? A creature? Do a little portrait study of this character. Have fun with this! Feel free to be inspired by our host of fairytale artists too!

Remember you can refer back to some of these artists here on our Pinterest board -

So excited to share this beautiful lesson from Donna Martin this month!

So many times as an artist, we think our work has to be “perfect”. We beat ourselves up if it doesn’t turn out just the way we want it or the way we expected it to. We tend to let the negative self-talk take over and sabotage the work we attempt to create. What if we created without expectations? What if we embrace the imperfection and create just for the pure joy of creating? That’s what this lesson is all about. That is the art of Wabi-Sabi.

One of my favorite things to do is to curate inspiration. From Pinterest boards to books, resources, playlists and more - I love to share anything that might facilitate learning, expansion, and sparks of curiosity! Being an artist, we naturally crave these things so here are some of this month’s picks from me to you.

Want to continue to geek about the history of Fairytale art - check this out -

More on artist - Arthur Rackham

I had so much fun curating this list. I hope you enjoy!!

Here are just a few of our fantastic classes! I highly recommend checking them out if you haven’t already. Enjoy!