Dear creative friends,

Welcome to Issue No. 47 of the Studioworks Journal! As always, I’m delighted you are here with me and I’m excited to share this with you. This month, I am once again inspired by my recent travels. On my recent journey to Ireland, I was so taken by the beautiful landscapes. I found myself gazing out the window at the sea and watching in awe as the light and colors shifted with the passing clouds. It wasn’t long before I had taken dozens of photos and began to make thumbnails sketches that I would create pastel paintings from. Quickly, I realized by stopping and observing the landscape, how my thoughts would quiet and my heart would slow. I found true connection to the land and the precarious beauty of the moment. I must admit, working plein-air and painting landscapes is relatively newer to me. Yes, I did it in Art school and on other occasions but I think this trip really solidified my desire to explore it further.

So this month, I want to pay homage to the art of being at one with the landscape. To expand on how we can create with the land as our Muse.

xo,

So you may be wondering, where do I start? To that, I say, wherever feels right to you. Each month we will have a theme, a creative affirmation, a power word, a color palette, sketchbook exercises, art projects, articles, recommended reading, and access to wonderful inspiration and resources. I want you to think of this as a delicious new magazine, you know the ones you occasionally splurge on, with soft, velvety pages, beautiful images, and inspiring content!

Each issue will invite you to explore your creative practice in whichever way works for you. Experience each issue at your own pace. Take what resonates with you and put the rest aside for another time.

Grab a cup of something lovely and dive in.

There are artistic methods that draw us close, beckoning us to study the detail in the curl of a petal or the curve of a hip. Others urge our eyes upwards and outwards, broadening our scope, and reminding us of the greater context, the bigger picture. Landscapes fall into the latter category, though detail is no stranger to this genre.

One of the beautiful aspects of landscapes is that they remind us to tune into where we are or consider where we would like to be. They attune our senses to the world around us and reveal the wonder that resides there, just waiting to be seen and appreciated. They can also help us to reflect inward, contemplating the inner landscape and its role in how we view things. Regardless, landscapes give us a sense of place and, in so doing, remind us of our relationship with the world around us.

In terms of the creative process, landscapes are a potent training ground. When you pay attention to the world surrounding you, the complexity of each living thing, the continuous changes in light, and the endless minute shifts in color and shadow from one moment to the next, it can quickly become overwhelming for the mind. How is it possible to capture even a fragment of that glory? You might find yourself wondering.

Asking this question is a good thing. It makes the task ahead a source of challenge, inspiration, and motivation, all at once. Landscapes bring our focus and awareness back to the intricately layered beauty of the natural world and remind us of how much wonder resides there. In addition, the striving necessary to recreate some fraction of what we see ignites the imagination.

It is this burning to create that we so often crave as artists. It washes away the dams that sometimes block our flow. In this way, it restores our drive to attend to the needs of our creative spirit, which is rooted in a deep yearning to convey our experience and make it tangible through expressing it to others.

In this way, landscapes offer us a challenge and a promise. They immerse us in our surroundings, increasing our sense of connection and inspiring us. At the same time, they compel us to strive to be our best to do justice to what we see and are attempting to capture.

ISome yogis spend their entire lives mastering a single pose. One that is frequently emphasized, gorakshasana, is chosen primarily because it is a process that enables a person to sit still for great lengths of time. This stillness is thought to move the practitioner in the direction of enlightenment.

In a similar vein, some of the earliest landscape art, which hails from sixth-century China, is from a style called shan shui, whose lasting power is demonstrated by its continued popularity to the present day. Believed to be inspired by Taoism, this art reflects a desire to evoke a sense of balance between humans and the natural world through the correct interplay of yin and yang. Though the requirements to achieve this style are manifold, and complex, the primary three components are winding paths, a welcoming threshold, and the heart, to which all the painting’s elements lead. Mastering this composition is a labor of discipline as well as love.

Shan shui can serve as a model for our own landscape art in many ways. For example, by increasing our focus, urging us to slow down, breathe deep, and consider with care the relationships between the things we observe, the purpose behind what we are trying to create, and why it holds significance for us, is revealed. Generating this presence can lead to heightened perception and, ultimately, it enables us to make better art.

Each era of landscape painting, from the Renaissance to Romanticism to the modern cityscape, can evoke this call to stillness and enhanced awareness. In part, because these qualities of concentration are necessary to meet the demands of landscape art.

You cannot capture the essence of unspoiled wilderness, the power of an electrical storm, or the energy of the setting sun without being a keen observer. Attaining this means learning to be still, fully inhabiting the present moment, and seeing what’s before you as it is.

As you embark on creating landscapes, you’ll be thrilled to discover how much there is to explore. For example, the dance of light reflecting off glittering waves, the span of color from green to crimson on Autumnal leaves, and the pristine mirror of a clear lake on a serene day. Every color on your palette will be required, and the changing light of each hour will confer new joys and present myriad challenges.

There will be no skill untapped as you attempt to depict the riffle on a stream or movement and energy of any kind. You’ll face the challenge of perfecting the source of light with appropriate contrast, brightness, and shadow. You’ll explore the range of colors on a single flower petal, from pale pink to the deepest crimson-black. As you practice recreating what you observe, or simply evoking an essence, your abilities as an artist will naturally increase.

Yet another wonderful thing about landscapes is that through creating them, you establish a habit of careful observation. With time this might lead you to see how each little segment of any scene could be a study all its own. It may then seem like a natural next step to deep-dive into explorations of texture, color, or composition by focusing on single elements.

Perhaps you will take up painting flowers, zooming in and magnifying them until they seem almost abstract in color and form (a la Georgia O’Keeffe). Or, maybe, you will become mesmerized by the grain of wood on an antique table or the countless fine lines on a loved one’s hand. When you become a keen observer, potential subjects reveal themselves everywhere.

What’s important here is not the subjects you choose to render but rather the practice you have initiated. By training yourself to look broadly, taking in the sweeping vista, you learn to encompass more in your vision. This broad view creates a valuable context that enables you to explore its natural corollary, the micro-view. Each way of seeing the world informs the other and improves your ability to bring your work from the esoteric realm of ideas into the living, breathing, landscape of your life.

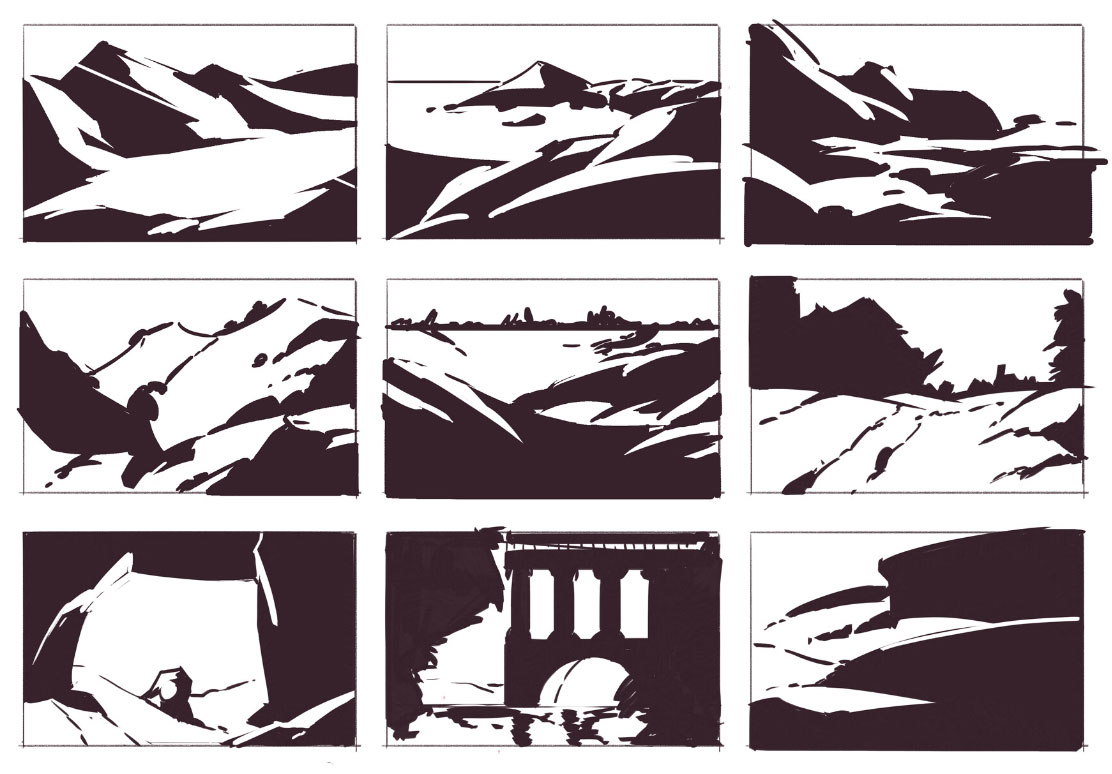

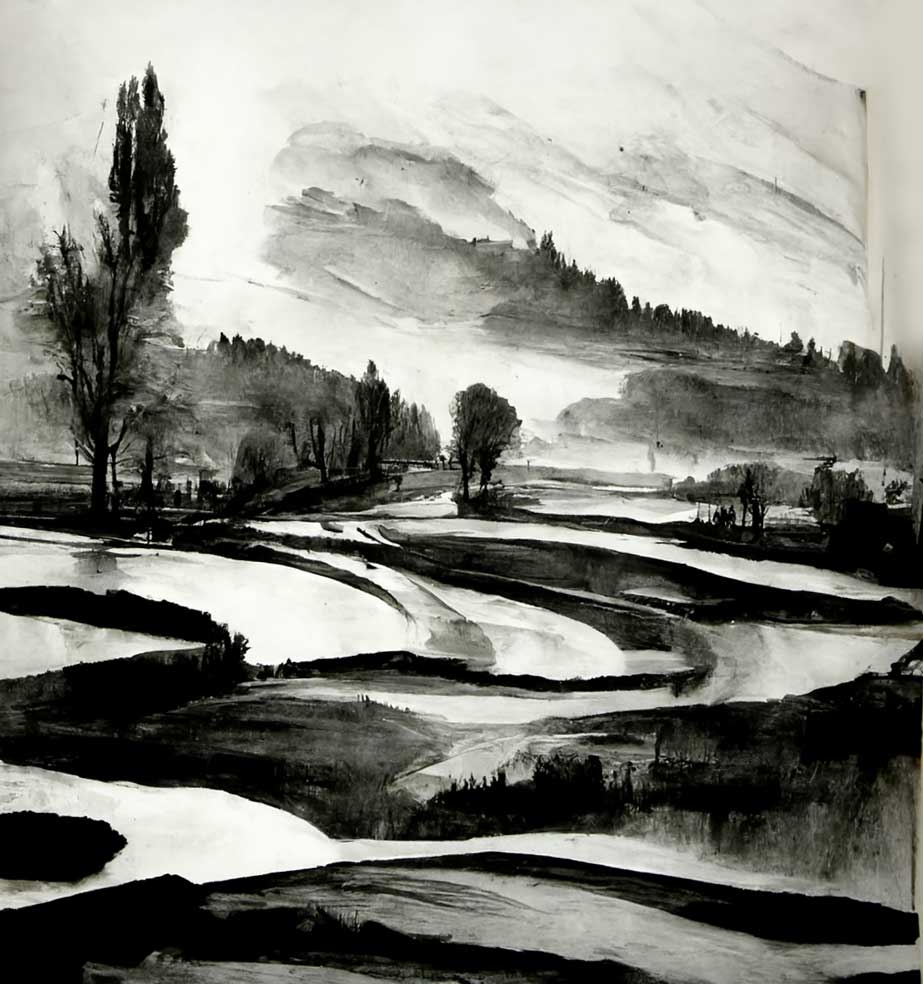

It’s not always the right choice to see things in black in white, but when it comes to the art of the Notan, it’s essential. Notan is a Japanese word for light-dark harmony or balance and, in art, serves as a framework for simplifying patterns into the two values of black and white.

A part of Japanese art for centuries, notan originated in traditional ink sumi-e paintings. This art form began with Buddhist monks, and as a result, the style emphasizes the virtues of simplicity and minimalism. These monochromatic paintings rely entirely on balancing light and dark since all shades stem from the level of dilution of the ink.

In addition to its obvious uses in ink painting, notan can be a valuable tool across art forms. The technique is often employed as a study, helping an artist to craft an image that is very deliberately and consciously designed based on their decision to categorize each element of the work as either light or dark.

It can sometimes be helpful to do a three or four-value notan if light and dark grey also feature prominently in the piece. Anything over four values is no longer Notan but instead a value study. Though there is overlap in these two types of studies, Notan is essentially about shape, design, and the effort to achieve a balance of light and dark elements in a work of art. The goal of notan isn’t realism. Instead, it encourages the artistic license to consciously limit what to include, distilling a composition into its essential parts.

Notan allows us to see the world in a simplified way. It helps to train the eyes to observe value patterns in terms of negative and positive space. This training aids the process of determining value structure in a painting and is central to a well-constructed piece. By reducing the values to two, it becomes easier to see the relationship between elements adding clarity and making harmony easier to attain. An image that elegantly demonstrates this is the yin and yang symbol, a classic notan illustration.

To practice, you can employ notan by composing a simplified sketch depicting only black and white. The overall composition will show the relationship, the patterns, and hopefully, the balance between the two. The more thoroughly you capture this dynamic, the better your notan will be. It is through the process of excising unnecessary detail that you determine the core features and essential components of your work.

Once you’ve mastered the elemental interplay of light and dark, introducing texture and color becomes icing on the cake, enjoyable but not required. Just as a building is only as solid as its foundation, a painting is only as good as its execution, and design is a central feature of that.

In the past, painters were confined to the studio, constrained by cumbersome materials and strict codes of discipline. The invention of portable easels and premixed paints, along with the adventurous, genre-challenging attitudes of young artists such as Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Alfred Sisley, and Frédéric Bazille, changed all of that. We can all give thanks for this.

Currently, it doesn’t seem particularly avant-garde to paint outside, but the inspiration of the beautifully ephemeral natural world retains its appeal, still awaiting our attention and our brushstrokes. If you’ve yet to attempt to paint en plein air, you might feel a little intimidated. Fear not, I’ve got you covered

The idea of not carrying more than you need evokes that Erykah Badu song where she discusses how carrying heavy baggage (emotional or otherwise) hurts your back. She then advises her listeners to “pack light.” Whether taking a trip abroad or painting outside, this advice is golden.

So, ask yourself what is truly necessary and leave the rest at home. It can even be part of the fun to limit yourselves to a few select colors, and a small canvas. You’ll want some kind of container, or ideally, a pochade box, to hold your supplies. Investing in a few mini palette cups and a mini brush washer is also handy. Gather a few compact paintbrushes, and then all you need is a gesso board, or some other primed and ready canvas, and an easel.

You could up your style and find a paintbrush holder for your easel and bring along a palette knife to save your brushes from the indignity of mixing paint. However, especially if you’re just getting started, make it a point to limit your materials. Allow your experience to inform you of what you need.

Painting locally is a wonderful opportunity to deepen your relationship with where you live. The simple act of being still, taking in a scene, and attempting to capture it in just a few hours will change how you see even the most familiar surroundings.

In addition, it takes away a common barrier to making art, namely, waiting for the perfect circumstances to begin creating. If you turn your artist's eye on the environment you regularly inhabit, your ability to be inspired gains endless sources, helping you produce more, and, perhaps more importantly, increasing the beauty of your daily experience.

You don’t have to be the next Monet to understand the value in evoking the energy of an image, rather than fixating on trying to reproduce every last detail you see. Though painting precisely can be a great way to train your hand, there is something to be said for forsaking exacting measures to seize the temporal nature of today.

If you want to finish a painting in the span of a few hours, as plein air painting invites you to do, you have to decide what is essential, and what can be expressed more loosely. This practice helps you to shed the fat from your work, honing in on what genuinely captures the essence you’re inspired to impart.

Remember, the world around you changes daily, and so do you. Each time you step outside and decide to honor that world by painting it, you learn something about yourself and everything that surrounds you. Doing this enriches your experience, helping you see more, thus improving your art and, probably, your entire life.

I chose this word simply because I believe it perfectly defines what happens when we still ourselves long enough to connect to the natural world around us - we enter into a state of communion. When we sit in the presence of the landscape, our inner space grows quiet as we observe light, color, shape, and shadow. There is indeed an exchange that takes place between you and the land. You may notice your breathing slows and the noise that once filled your inner world is replaced with birdsong, the babbling of the nearby stream, or the wind through the trees. Your thoughts, once preoccupied with your own inner musings, turn outwards and now ponder the shape of clouds, the starkness of the mountains, or the curl of the waves.

This is when an artist’s senses are heightened. When we can call forth that visceral drive to create something - if only we can capture the blue of the sky, or the light glowing on the horizon or the red of the poppies in the distant field. This hunger for beauty drives us deeper in our communion with the land and pushes us to put paint to canvas. To push past our own fears and trust in our hands and our eyes and our hearts.

I am sharing this beautiful Meditation from one of my favorite meditation masters - Rachel Hillary. Give yourself about 30 minutes to experience this wonderful grounding meditation.

Rachel will share a little about this experience -

This guided visualization leads you to a vibrant and uplifting journey, to connect your roots with the roots of the earth, gaining sustenance, feeling nurtured, activating magic inside of you, and also giving back love to support the earth, and receiving the wealth of the earth in return. This visualization takes place on some beautiful red rocks, warmed by the sun. Immerse yourself in this meditation adventure. Radiate red, reclaim your power.

lots of love,

Rachel

Each month we will have a positive affirmation. I recommend you print out this affirmation and put it in your sketchbook or somewhere in your studio. Recite the affirmation out loud each time you show up to create. Saying words aloud is powerful and can begin to re-write some of our own limiting beliefs or calm our fears. Try it now…

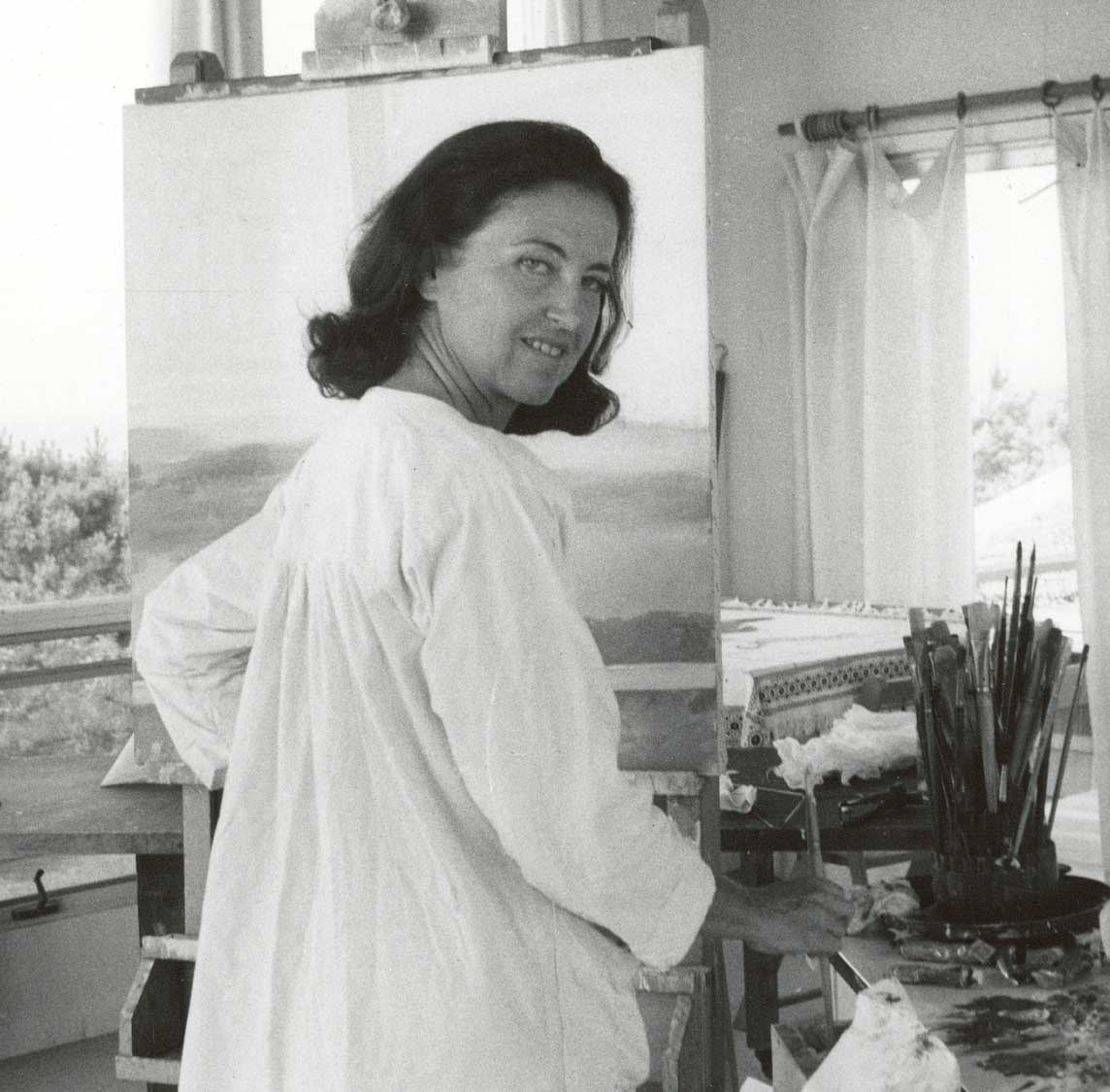

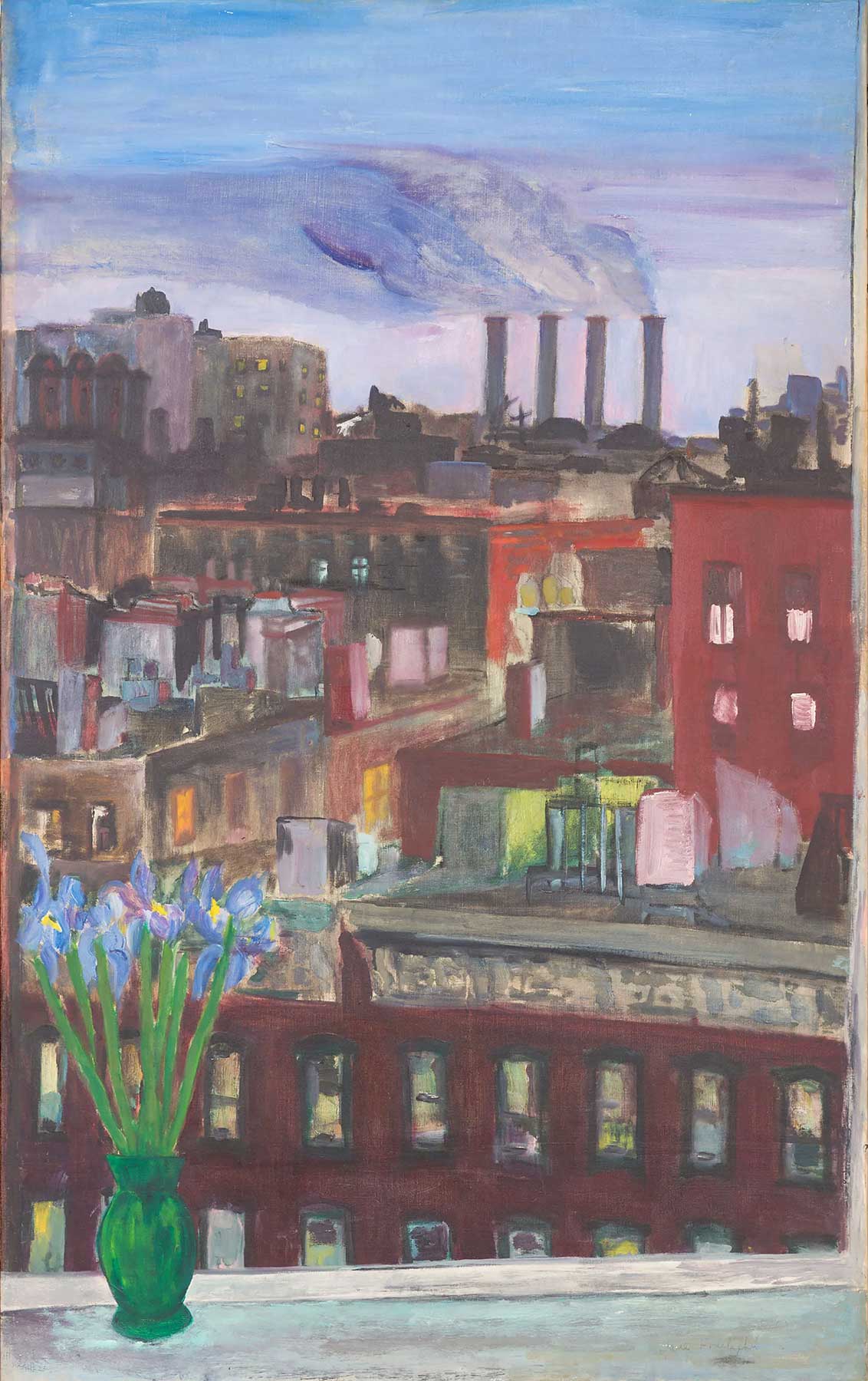

This month I am inspired by the wonderful works of our featured Master artist of the month, Jane Freilicher. Her beautiful scenes of both still life and landscape are created in soft natural tones that evoke a sense of intimacy and peace with the scene. Soothing landscape shades of warm and cool greens, soft yellow ochre, and sky blues are given a distinctly feminine energy when paired with delicate lavender and gentle pinks. Of course, while I encourage you to use the colors of the landscapes in your own world, these will be the shades I will personally explore this month.

When it comes to landscape painting there is a huge list of artists to choose from, so you may wonder why I chose Jane Frelicher? I chose her for several reasons but I must admit, I like to select artists you may never have heard of before! Bringing light to these more obscure (and often female) artists is a joy for me because many times, they are NEW to me too and so we are learning along together!

I also chose her because I found myself quite captivated by her scene that joins the interior world with the exterior. You will witness that in many of her works she pairs an interior still life on the edge of an exterior landscape view - thus marrying together inner and outer. This to me is rather profound and poetic. While the interior still life, like a vase of roses and a bowl of fruit, is arranged by human hands - the exterior landscape is that arranged by nature herself. One part is controlled by us the other is governed by the land. While we may orchestrate our interiors we are always beholden to the wildness of the exterior landscape. This connection is poignant and offers deeper thought and creative exploration. So as we let that simmer within, let’s learn more about this fabulous, contemporary artist…

Jane Freilicher was born in the Flatbush section of Brooklyn in 1924. The only girl in a large family, she was coddled by her parents. Her mother was an amateur pianist who played in silent movie theaters before marrying. Her father was an Eastern European immigrant and a Spanish- and Yiddish-language court translator. His love for his daughter's drawings "was a kind of encouragement to go into the arts," Freilicher remembered. In particular, Freilicher liked flowers; she remembered, "When I was a child my parents used to give me little bouquets. I liked to contemplate them, wonder about them." Her brother often brought home issues of Verve magazine, which featured high-quality reproductions of works by artists like Picasso, Matisse, and Miró, and she wondered if she couldn't make art a career for herself.

After graduating high school (as class valedictorian) in 1941, she eloped with Jack Freilicher, a jazz pianist who played with the Army Band at West Point during World War II. Their marriage did not last long, however, and was annulled in 1946. Through Jack she met Larry Rivers, a painter and jazz musician with whom she was later romantically involved, and painter Nell Blaine.

Freilicher attended Brooklyn College, earning her B.A. in 1947. Working towards her degree and now divorced, she did odd jobs, and she recalled, "Somehow I struggled through the lean years. It was fun - and a terrible hardship at the same time." At the urging of Rivers and Blaine, she relocated from Brooklyn to Manhattan. She earned an M.A. from Teachers College, Columbia as a safety plan but was spending more and more time painting.

Immersed in the exciting downtown art world amidst the burgeoning Abstract Expressionist movement, and at the urging of her friend Nell Blaine, Freilicher began studying with the famous painter and teacher Hans Hofmann. Freilicher loved how democratic the studio was and recalled how Hofmann's teachings "brought a kind of melding of the modern with tradition." This resonated with her even more deeply when she saw the Museum of Modern Art's 1948 Pierre Bonnard show; she appreciated Bonnard's "sensuousness and intimacy" as well as his treatment of everyday objects and interiors.

Freilicher decided that Abstract Expressionism's elision of representation and narrative was not for her, admitting "I couldn't find a kernel in that kind of painting to split open. I have to struggle, to make something coherent, so the work engages me and leads me into some kind of struggle... I felt I couldn't find a struggle within Abstract Expressionism." Instead, Freilicher painted interior and city scenes, portraits, still lifes, and landscapes, all with an expressive, meditative, and lush painterly hand. This placed her within the loosely-knit group of artists considered Contemporary Realists, though Freilicher deemed her own work "painterly realism."

Freilicher's first solo show was at Tibor de Nagy in 1952 and received positive reviews. Writing for ARTnews, fellow painter Fairfield Porter deemed her work "traditional and radical" and extolled the work for being "broad and bright, considered without being fussy, thoughtful but never pedantic."

Amid the larger-than-life personalities of the New York School, Freilicher continued with her own work, rooted in the world of quotidian objects and had no problem, in her words, "[standing] to the side a little, where I was anyway, and [going] on with what I was doing."

One day in 1949, the poet John Ashbery, newly arrived to the city, knocked on Freilicher's door. He was picking up a key to the apartment of his college friend and fellow poet Kenneth Koch, who lived a floor below Freilicher. Freilicher invited Ashbery in for coffee, and this encounter led to a lifelong friendship, one that was mutually beneficial on a creative and emotional level. Ashbery called her "the wittiest person I have ever known," "screamingly funny," and "probably my favorite person in the world." He lauded her way of painting that was "constantly different, fresh, and surprising."

Freilicher took her new friend to Rudy Burckhardt's shoot for his short film Mounting Tension (1950), which she and Ashbery ended up starring in along with Larry Rivers and Ann Aikman. Freilicher liked acting and also starred in Burckhardt's The Automotive Story (1954).

Despite the stylistic differences, Freilicher was ensconced within the New York School, a term usually meant to be synonymous with Abstract Expressionist painters but was in reality far more diverse and included a host of other artists, including poets. As writer Jenni Quilter explains, "Freilicher occupied a singular position, inspiring an unparalleled devotion among her friends, particularly the poets." Frank O'Hara, in particular, wrote numerous poems for Freilicher such as "A Sonnet for Jane Freilicher," "Interior (With Jane)," and "Chez Jane."

Freilicher married Joseph Hazan in 1957. Hazan was a wealthy clothing manufacturer and painter as well as a former dancer. The couple had one daughter, Elizabeth. Freilicher began spending more and more time in Long Island starting in the 1950s; Hazan built her a house in the small hamlet of Water Mill. There she painted still lifes and landscapes, a perfect corollary to her Greenwich Village city scenes.

Though Freilicher spent the rest of her life alternating between Greenwich Village and Long Island, she also had opportunities to travel. She went to Europe three times in the 1960s, visiting Ashbery in Paris each time, as he had relocated there. Together they went to Sicily, Barcelona, and the French countryside, as well as Spain and Morocco.

Freilicher enjoyed raising her daughter (who later became an artist herself) and did not see motherhood as an impediment to her own artmaking. Being older and more financially secure when she had Elizabeth helped, but she also explained, "Even though my daughter was the most important thing, I never felt that I had to do everything, and be everything for her - I never had to take her everywhere and provide her with every conceivable lesson, the way so many parents do today."

In 1975, Freilicher was one of 45 artists commissioned by the Department of Interior to make work for the travelling exhibition, America 1976, a show commemorating the country's bicentennial. Instead of travelling to paint an American scene, she decided to paint the familiar landscape of Long Island. She remarked, "I have to feel comfortable where I am.... I have to burrow in and feel at home." She was so closely identified with Long Island during her lifetime that the East Hampton museum, Guild Hall, honored Freilicher with a Lifetime Achievement Award in 1996, and in 2005, she received a gold medal for painting from the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

Freilicher painted for the rest of her life. When asked in 1998 at the age of 73 about her decades-long preference for her subject matter, she stated amiably, "I suppose I'll just keep doing what I'm doing. Even though I'm using ostensibly the same subject matter, I keep on trying to get some other kind of sensation from it. Every flower has its own cosmology, its own relationship to the foliage, to the air around it."

In 2014, Freilicher died in her Manhattan apartment at the age of 90 due to complications from pneumonia. A December 12 birthday party hosted by the Poetry Project at St. Mark's Church went on as planned, becoming a celebration of her life and work. Eric Brown of Tibor de Nagy Gallery, the space in which she exhibited the entire length of her career, said upon her death, "An extraordinary artist and an exceptional friend, Jane will be profoundly missed. We will never forget her wit, her acute intelligence, her integrity and grace."

In pursuit of realism, Freilicher, by remaining true to herself, inspired other painters of her era such as Grace Hartigan, Fairfield Porter, Milton Avery, and Hedda Sterne in their engagements with representation. She was also profoundly important to the poets with whom she surrounded herself, such as John Ashbery, James Schuyler, Kenneth Koch, and Frank O'Hara. Their poems about her and for her are a testament to her wit, creativity, warmth, and self-confidence.

Here is one poem about Jane by her poet friend, James Schuyler :

Though her reputation ebbed and flowed throughout the latter part of the 20th century, as art movements privileging sculpture, abstract painting, video, and installation unfolded, she remains a "painter's painter" and came to inspire feminist artists who admired her unabashed focus on private spaces and intuition as well as contemporary painters of still lifes and interior scenes, such as Jonas Wood, Rebecca Scott, and Tracy Miller.

Go ahead and get out into your world and do a little plein air sketching or painting. While this can be intimidating (and yes I am still very intimidated by it) it can also be incredibly fun and relaxing. Remember to limit your materials, simplify what you see and choose what you want to focus on. You are the boss! You don’t have to draw realistically or accurately to enjoy this process and create some fun pieces. Just look at how our master artist, Jane Freilicher flattens perspective, simplifies the landscape or allows some things to be less defined. Alternatively, if you are unable to work plein air, then work from photographs of your surrounding area or favorite spot in nature.

Here are some of my plein air photos from my travels this year...

Do a Master study of one of Freilicher’s paintings or create something inspired by her. You could set up your own still-life arrangement in front of your own window and paint the view. Keep it simple and spend some quiet time reflecting on the connection between our inner and outer landscapes. What happens in the liminal space between? In Freilicher’s works, this boundary is often represented as a window. A symbolic element indeed! As with Freilicher’s work, find beauty and that spark of inspiration in your scene and use that energy to begin the piece. Don’t feel confined to realism but rather express your view in the way you want to.

Either from real life or photographs create some thumbnail notan sketches to illustrate the light and dark of a scene. How do these shapes relate? How can you alter the design to create a stronger composition? Things to avoid…objects smack in the middle of the canvas, shapes too close to the corner of your substrate, choose an odd number of shapes over even (i.e. Three trees as opposed to four). Look and see how the light and dark shapes interact. Some questions to ask - Does the composition feel balanced? Do the shapes of light and dark lead the viewer into the landscape? Is there a sense of rhythm to the shapes? Refer back to our notan article if needed or watch this great video on the importance of the Notan.

Refer back to our notan article if needed or watch this great video on the importance of the Notan.

So excited to share this beautiful lesson from Nicole Warrington this month!

The color and light of autumn is in full swing in the Northern hemisphere, surrounding us with the glow of pinks, golds and oranges. It’s always such an inspiring sight, and the dancing light is so wonderfully captured in watercolor. Let’s use this lovely medium and a gorgeous fall palette to create a painting that honors the fleeting moment and the beauty of nature.

One of my favorite things to do is to curate inspiration. From Pinterest boards to books, resources, playlists and more - I love to share anything that might facilitate learning, expansion, and sparks of curiosity! Being an artist, we naturally crave these things so here are some of this month’s picks from me to you.

Love Ian Robert’s Videos on Composition and Simplification (he has tons of videos)

I had so much fun curating this list. I hope you enjoy!!

Here are just a few of our fantastic classes! I highly recommend checking them out if you haven’t already. Enjoy!