Dear creative friends,

Welcome to Issue No. 46 of the Studioworks Journal! As always, I’m delighted you are here with me and I’m excited to share this with you. This month, I wanted to do something a little different. We have touched on several art movements within the Studioworks Journal but I’ve never dedicated an entire issue to one! So, in this issue, we are going to focus on the art movement of Japonisme. This fascinating time of cultural exchange during the late 19th century produced incredible artworks and inspired so many of the artists you know and love, including Gustav Klimt, Vincent van Gogh, Claude Monet, Mary Cassat and Edgar Degas to name just a few!

If all of these artists were influenced by Japanese culture, than surely we can gain much inspiration by taking a closer look at this passage in Art History. So, let’s dive in together!

xo,

So you may be wondering, where do I start? To that, I say, wherever feels right to you. Each month we will have a theme, a creative affirmation, a power word, a color palette, sketchbook exercises, art projects, articles, recommended reading, and access to wonderful inspiration and resources. I want you to think of this as a delicious new magazine, you know the ones you occasionally splurge on, with soft, velvety pages, beautiful images, and inspiring content!

Each issue will invite you to explore your creative practice in whichever way works for you. Experience each issue at your own pace. Take what resonates with you and put the rest aside for another time.

Grab a cup of something lovely and dive in.

There is something timeless about the allure of forbidden fruit. Anything denied can become a source of unlimited intrigue. Along this line, what could be more fascinating than a culture shrouded in mystery that had denied visitors for roughly 250 years? This was the backdrop of Japan’s resumption of trade with the West in the 1850s.

The sudden accessibility to the vastly rich and diverse culture of Japan, with its highly stylized art and design, sent Europeans into a frenzy of creative expression all their own. This craze for all things Japanese led the art critic Philippe Burty to coin the term Japonisme in 1872.1

Like the great wave of Kanagawa foretold, with its symbolic message of societal change from encounters by sea, Europe was inexorably altered by contact with Japan. This was precisely what the Japanese had feared happening to them if they opened trade with the West. Clearly, they weren’t wrong, and also, influence is a two-way street.

It’s no exaggeration to say that this era ushered in a monumental shift in European sensibilities that affected everything from clothing styles to building design to landscaping, not to mention theatre and art. In many ways, it seems that impressionism is the creative child born of Monet’s fascination with the flatness, color, realism, and stylization of Japanese woodcut prints.2

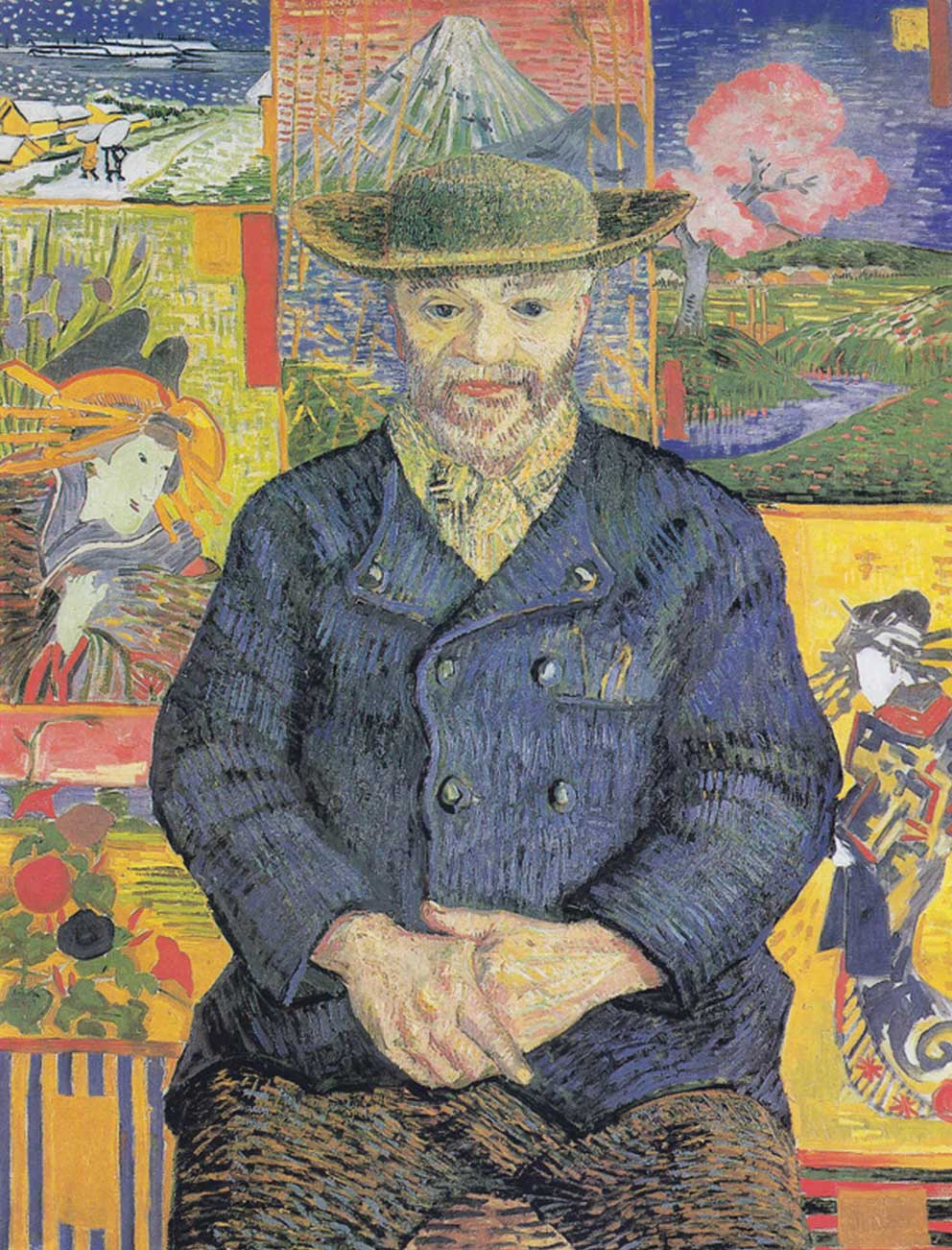

Post-impressionism also owes much to this influence. Vincent Van Gogh, an iconic artist of this period, sums this up nicely in a letter to his brother Theo, “All my work is in a way founded on Japanese art... Japanese art, in decadence in its own country, takes root again among the French impressionist artists.“

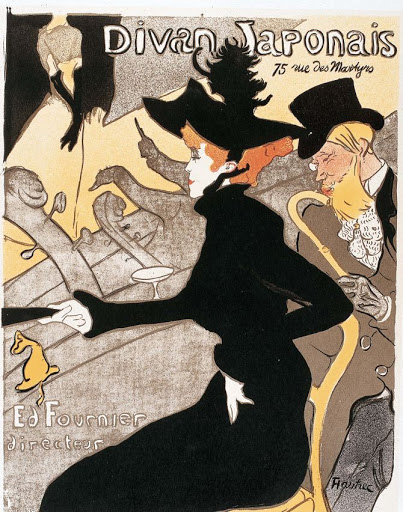

Toulouse Lautrec, a contemporary and friend of Van Gogh, was also deeply impacted by Japanese woodblock prints, particularly those of the Ukiyo-e artist Utamaro from the Edo period. Also called the floating period, the art of this time centered around amusement quarters, a theme mirrored by Lautrec’s paintings of Parisian nightlife and brothels.

Another gifted artist, who owed much of his style to Japanese art, was the Viennese powerhouse, Gustav Klimt. He was a great collector of prints, ceramics, and facemasks from Japan.5 His use of gold leaf, and wood block-inspired designs in his paintings, caused a sensation in Austria. A part of the Viennese Succession, his works emphasized the values of craftsmanship over mass production, embracing a deliberate philosophical shift in the art of Vienna.

It would be reductive to suggest that Japonisme was simply the result of the novelty of contact with a foreign culture. The broader reason European artists were so profoundly influenced by contact with Japan seems to be the allure of creative freedom. Japanese art liberated Western artists from the constraints of mathematical perspective, highlighted the use of bright colors, pushed back against the uniformity introduced by the industrial revolution, and emphasized the beauty of the natural world.

As creatives, it can be easy to fall into the trap of believing there are right and wrong ways to make art. This can lead to an elusive idea of perfection, promoted by the need for social approval, and create hard lines around what and how you create. This is where seeing works of great beauty, that flout all your expectations and presuppositions, can set you free.

In a certain sense, Japonisme is a reminder of this. A call to let loose, while also deeply respecting form, function, symbology, and craftsmanship. There are no set rules defining what is beautiful. Foreign cultures can sometimes reveal this, and in so doing, take the world by storm.

When considering the island nation of Japan, many images are likely to spring to mind. Beautifully landscaped gardens, stunningly conducted tea ceremonies, artfully presented food, bright colors, and flashing lights, to name a few. Along with the imagery, there are concepts like order, efficiency, excellence, and discipline that Japanese culture evokes.

When you look more closely, the overarching theme becomes one of conscious creation. Japanese people strive to live by design rather than by accident. This principle is thoroughly reflected in the nine Japanese aesthetics1,2:

Together these aesthetics comprise a comprehensive strategy for both interpreting and creating art. Developing a philosophical framework for what you want to achieve, which also depicts why it matters, is a potent way to deepen your connection with each creative endeavor you embark upon. This strategy for cultivating meaning is well worth exploring.

As an artist, it should be pretty straightforward to see the value in embracing the first aesthetic of Wabi-sabi. How many times have you stalled out on a project because there was some part of you that couldn’t accept that it was fully complete, or quite good enough? Falling prey to the “never finished” syndrome can leave a destructive wake, most notably by impeding the creative spirit.

Wabi-sabi gracefully eliminates this problem by deliberately looking for beauty in what IS rather than chasing the phantom of perfect. By no means does this reduce the pursuit of excellence. Rather, it allows you to see the loveliness of the fleeting moment, the glory in a rain of blossoms, or the brilliance of leaves in fall, without a negative focus on what follows.

Aspiring to create an elegance of form, eschewing vulgarity and crudeness, can elevate one’s creativity. This doesn’t have to be an austere and cold process, but rather a highly personal one. What gives you the sense of being your best and avoiding what you deem absurd? That is your Miyabi.

Western culture often celebrates an over-the-top, in-your-face kind of expression. In this, shibui can be a needed balm. Emphasizing subtlety, simplicity, and unobtrusiveness brings a more nuanced perception to an artist’s work. In so doing, attention to detail and taking great care in what you include can add richness, texture, and, ultimately, a kind of complexity within simplicity. This quality of contrast, is part of the line shibui walks, adding interest and timelessness to your work.

In many ways, cultivating uniqueness and originality is a boon to creativity. If you are eager to emphasize what makes your creations your own, it frees you from comparison with others. Another inspiring facet of iki is fostering subtlety. For example, you might incorporate something in your work that is only meaningful to you, or select others, making the piece quietly and uniquely expressive. This process also creates freedom because the rewards reaped are internal.

As a concept, beginning something slowly, then moving rapidly, and abruptly stopping, emphasizes the appeal and drama of change. It might be easier to see how this aesthetic might apply to film, music, or theatre, but even in painting, this tempo could be employed. Simply focusing on tempo in your work could introduce myriad new ideas and behaviors.

In a sense, yūgen could be a reminder that it’s ok to leave things to the imagination. Sometimes retaining a shroud of mystery is the best form of artistry. Failing to explain, or depict every detail, can be just the necessary spark to ignite inspiration for the mind.

Discipline is one of the dearest friends of the artist, whether you know it or not. Creating a system you adhere to can keep you dedicated and moving forward, helping you retain a practice unimpeded by the changing tides of the world around you. This commitment you make to consistently and deliberately employ your craft is what separates makers from dreamers.

To embrace this aesthetic is to embark on a journey of minimalism that simultaneously incorporates the infinite. It’s heady stuff, pregnant with possibilities for artistic expression.

In Japanese calligraphy, it is a circle painted with a single stroke. It can be open, indicating movement and development, or closed, denoting perfection. It is an opportunity for the mind to let go and allow the body to create.

Making art, that is cute, lovable, and adorable is inspiring, in part because it’s fun. It takes away the pressure of seriousness and promotes inclusiveness. It might not be how you always want to create, but it’s a wonderful component to introduce from time to time because it reminds you of the art of play.

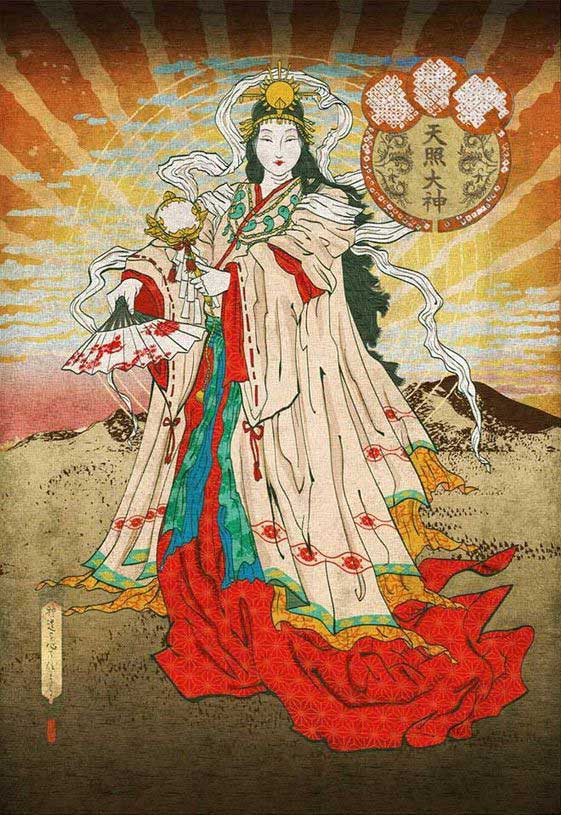

As many of you know, I adore mythology and I often find inspiration in cultural stories about various gods and goddesses. So since we are exploring Japanese culture and the movement of Japonsime, I thought it would be fitting to learn more about the goddess, Amaterasu.

Amaterasu is the great and glorious goddess of the sun. The Japanese Imperial Family claims to have descended from her, and this is what gives them the divine right to rule Japan. An embodiment of the rising sun and Japan itself, she is the queen of the kami and ruler of the universe. Though she did not create the universe, she is the goddess of creation, a role she inherited from her father, Izanagi, who now defends the world from the land of the dead. Amaterasu is married to Tsukuyomi, her brother and the god of the moon, forever separated after his murder of the goddess Uke Mochi.

As sun goddess, she not only serves as the literal rising sun that illuminates all things but also provides nourishment to all living creatures and marks the orderly movement of the day into night.

At one point in her story, she fled to a dark cave because she felt the world was too harsh and cruel (this may have been symbolic of Winter or an eclipse). All the goddesses and gods begged her to return with her life-giving light but she refused.

Uzume, the God of Merriment arrived at the mouth of the cave to inform Amaterasu just how severe things had gotten on Earth without her light. Uzume began to dance and shout things to try and get her to come out, he finally succeeded by holding up a mirror to Amaterasu to show her the beautiful light she was withholding from the world. She agreed, emerged from the darkness and the light returned.

Amaterasu is an important part of contemporary Japanese religious life, most notably worshipped at the Ise Grand Shrine, which is rebuilt every twenty years. This Shrine (known commonly as Jingū) is not only Japan’s most historically important shrine, but also the official shrine of the Imperial Family. Dedicated to Amaterasu, this shrine houses the Imperial Regalia and was an important site of pilgrimage throughout the Edo Period (1600–1868). There are several sections of the shrine where only priestesses and members of the Imperial Family may pass. As such, the shrine’s chief priest and priestess must be of the Imperial Family line.

Check out this Pinterest Board dedicated to Amaterasu

The Japanese have many forms of creative expression, one of my favorites is the art of Haiku poetry. Like visual artists, these poets must express emotion, description, and illumination but with only a few words. Challenging, yes, but so inspiring as well! Let me tell you a little bit more about Haiku.

Haiku is a traditional, unrhymed, and structured short form of Japanese poetry which has fixed rules that apply to its composition. Haiku poetry is well known for the 5/7/5 rule, consisting of five syllables in the first line, seven in the second, and repeating five in the third.

Overall, a Haiku’s structure consists of 3 lines and 17 syllables, which you cannot exceed. Other traditional rules used to be that a Haiku should refer to a season of the year, with an element that signifies that season: flowers, blossoms, wind, or rivers, and that you should avoid the use of similes or metaphors within the poem.

Although in traditional Haikus these rules still may apply, nowadays other themes are also practiced and accepted as long as the poetry relies on simplicity. Yes, simplicity, depth, lightness, and intensity, all expressed through 3 lines of poetry! Sounds difficult right? And that’s exactly what makes Haiku so precious in Japanese literature and also worldwide. Through those lines, a haiku poet is able to paint a vivid picture for the reader, using the most exact and profound words to describe his experience. Haikus focus on a brief moment in time, juxtaposing two images, and creating a sudden sense of enlightenment.

Over the wintry

Forest, winds howl in rage

With no leaves to blow.

- Natsume Sōseki

The light of a candle

Is transferred to another candle—

Spring twilight.

- Yosa Buson

A world of dew,

And within every dewdrop

A world of struggle.

- Kobayashi Issa

While it was tempting to make all nine of the Japanese aesthetic values our words for the month, I had to choose Elegance (Miyabi) as one for us to ponder, since I believe it encompasses many of the other values. Japanese art, if nothing else is the epitome of elegance. Restrained, balanced, authentic, and pure, it’s no wonder it captured the hearts of so many artists when they first encountered it. I believe we can greatly learn to apply some of these values to our own art. The Japanese know that what is on the page is important but what is NOT visible has equal importance. What we chose to include in our works and what we leave out intentionally gives intention and purpose to our vision.

Elegance is not about overdoing it or layering on everything but rather it requires using only what is truly necessary to express what is wanting to be expressed. Refining our vision, our compositions, and our use of line and color is key to creating truly elegant artworks. So next time you are drawing or painting, consider….what needs to be seen, and what does not? Edit your work. Just like with beautiful music or lyrical poetry, create harmony, balance, and elegance in your visual arrangements.

I am sharing this beautiful Meditation from one of my favorite meditation masters - Rachel Hillary. This one is so serene and reminds me of some the mountain temples of Japan, surrounded by lush, green forest where mystical deer roam freely and birds sing sweetly. How magical to be there now and to experience the deep peace…let’s take a journey and do just that. Give yourself just 20 minutes to connect within.

Rachel will share a little about this experience -

This guided practice for grounding takes place deep in the lush green forests, full of animals and magic. As we connect together to the roots of earth magic, this energy is channelled through for you to receive and to embody after the meditation is over. We meet an animal guide, with messages of love and earthly mystery for you, allowing space for you to connect. This simple and steady exercise is full of magic, and earthy green tones that are ready to flow through you. Please note: there is no ending bell, the music simply plays on for a few minutes and then fades out.

lots of love,

Rachel

If you enjoyed this meditation, you could also try Shinrin Yoku also known as Forest Bathing.

What is forest bathing? This Japanese practice is a process of relaxation; known in Japan as shinrin yoku. The simple method of being calm and quiet amongst the trees, observing nature around you whilst breathing deeply can help both adults and children de-stress and boost health and wellbeing in a natural way. An artist can gain much from this peaceful practice.

Each month we will have a positive affirmation. I recommend you print out this affirmation and put it in your sketchbook or somewhere in your studio. Recite the affirmation out loud each time you show up to create. Saying words aloud is powerful and can begin to re-write some of our own limiting beliefs or calm our fears. Try it now…

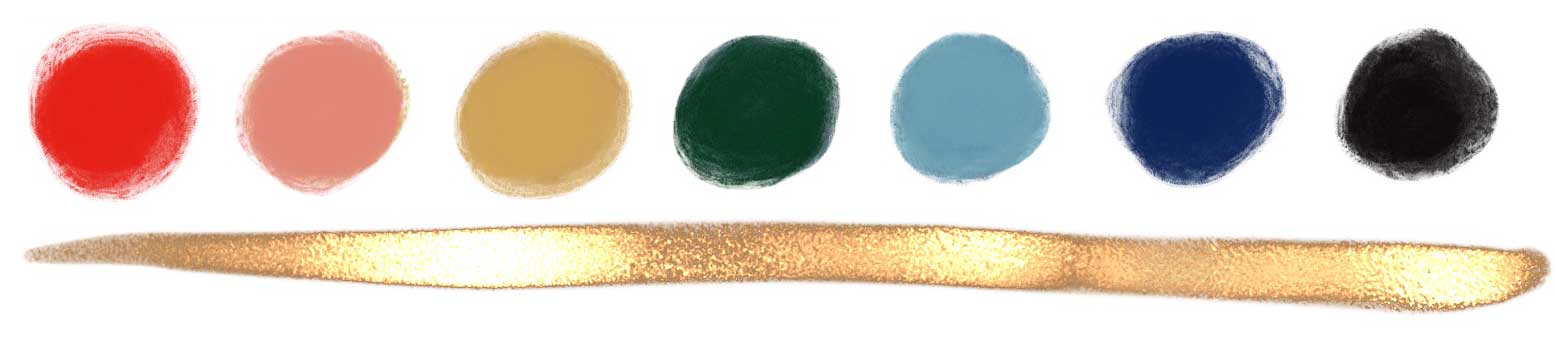

This month, as we are being inspired by a movement, rather than one singular artist, I have curated a palette that I think resonates. Nature is a constant theme in Japanese art so these hues reflect this regard for the beauty of the natural world.

Deep pine green, sky blue, ocean sapphire, the grey of mountains and mist, black onyx, feather white, ochre earth, scarlet red, petal pink, and of course, shimmering sun gold.

As always, work with colors that call to you and never doubt your creative intuition. Your colors may look entirely different and that’s ok.

Japanese art has a long history and like most cultures has a vast array of masters, styles, and periods. However, I wanted to bring to you just three of the greatest Japanese artists whose incredible talent inspired many of the European artists that we know today.

Katsushika Hokusai, better known simply as Hokusai, is the artist one knows without knowing him. The artist was ukiyo-e (woodcut designer) and printmaker during the Edo period, who depicted the now incredibly famous images of Mt Fuji (an obsession of his), and The Great Wave to name just a couple. Western Impressionist artists such as Monet, Van Gogh and Renoir were greatly influenced by Hokusai’s works, particularly his composition and his use of color. In his lifetime, the artist produced roughly 34,000 works of art.

Known for his work in ukiyo-e and bijinga okubi-e (paintings of beautiful women with large heads), Utamaro Kitagawa is credited with some of Japan’s most famous and well-known pieces of art. Although his personal life and history is somewhat shrouded in mystery, what is left behind is a substantial 2,000 paintings, each displaying his unique approach of painting subjects with exaggerated features. There are no records of him, be it letters, diaries, or legal documentation, but there are many theories and speculations bequeathing him titles like “a mastery of femininity,” and an “expert on women.”

The Japanese landscape artist, Hasui Kawase, was active in the Taisho and Showa era of the early 20th century. Hasui was known for his woodblock ukiyo-e prints and participating in the shin hanga (new prints) movement. His artwork reflect his love for the breeze. The scenery of Japan’s distinct four seasons can be found in his work as well. Hasui, in his delight for soft breezes, evokes a poetic lightness in his pieces, which are often thought to be soothing and calming; a respite for those caught up in the busy day-to-day of city life.

Enjoy a slide show with more work by these three Japanese masters plus art created by European artists during the time of Japonisme.

(and the corresponding Studioworks Journal where we have studied this artist)

(and the corresponding Studioworks Journal where we have studied this artist)

With our monthly goddess, Amaterasu, as our muse, let’s create a portrait or expression of this powerful Goddess (or one you choose to work with). Feel free to use any medium that brings you joy! How can you envision yourself bringing light into your creative life just like the Sun Goddess that Amaterasu is. Feel free to use some fabulous gold paint with this one!

Check out our curated Pinterest board to get your creative ideas flowing...

Look over our slideshow and Pinterest boards and see if you can create a Japanese-inspired portrait or landscape. What intrigues you the most about the nine Japanese aesthetic values? Jot this down in your sketchbook and explore why this is…how can you bring more of these values into your own work? Do you relate to the European art created in the Japonisme style? Create a second study or piece based on this movement. Spend some time in this period…there is much to absorb.

Now I know most of us don’t consider ourselves poets but why not try a little Japanese Haiku poetry OR if you really aren’t feeling it, then how about illustrating a Haiku poem! You can find beautiful ones all over the internet. Here is a link to one source to get you started...

The poem I chose to illustrate is this one...

love between us is

speech and breath. loving you is

a long river running.

- Sonia Sanchez

So excited to share this beautiful lesson from Dena Ann Adams this month!

The color and light of autumn is in full swing in the Northern hemisphere, surrounding us with the glow of pinks, golds and oranges. It’s always such an inspiring sight, and the dancing light is so wonderfully captured in watercolor. Let’s use this lovely medium and a gorgeous fall palette to create a painting that honors the fleeting moment and the beauty of nature.

If you'd like to be featured in an upcoming Studioworks Journal, we'd love to have you join our Creative Network! Our intention with Studioworks has always been to cultivate community involvement and collaboration. Featuring members from our creative community is such an honor and a beautiful way to share the light you all bring. Come join us!

I had so much fun curating this list. I hope you enjoy!!

Here are just a few of our fantastic classes! I highly recommend checking them out if you haven’t already. Enjoy!